The Future of History in the Pandemic Age

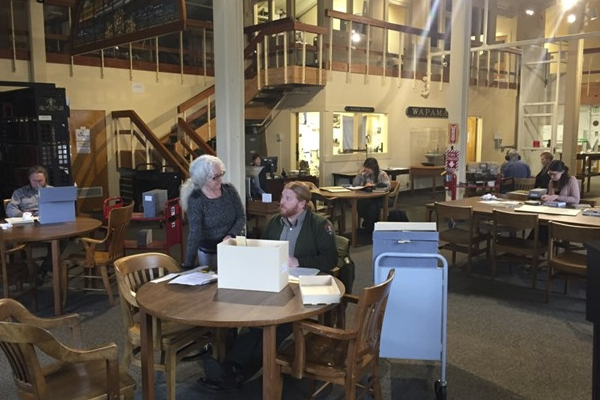

Reading Room of the Maritime Research Center, San Francisco

Attempting to predict the future is always perilous, and events frequently humble those who dare to try. Making predictions is especially hazardous for historians, who often struggle to explain the past. Peering into the future is not part of their professional training, and their efforts to do so are likely to fail.

But the need to prepare for an uncertain future forces us to think ahead. For historians, the most immediate question is how COVID-19 will affect the profession of history. Though the answer depends on several things—the timely advent of a safe, affordable, and effective vaccine being chief among them—a number of changes to the profession are almost certain to occur.

One big problem facing historians is that conducting research will become more time-consuming. Unlike scholars in some other fields, historians normally have to travel to conduct their research. Archives will likely institute hygiene-related protocols, which will increase the time historians must wait to gain access to documents. Moreover, reading rooms in archives may admit fewer researchers at a time, which would involve further delays. These and other COVID-related measures could significantly slow the pace of archival research.

The additional time needed to do research will make it more expensive as well. Archives are often located in major cities, where the cost of living can be quite high. Though the current lower cost of short-term lodging reflects a diminished demand, prices will probably rise once the pandemic is under control. This could result in scholars spreading out research trips over multiple years, thus lengthening the time needed to complete dissertations, books, and articles. The tenure clock might have to be extended to compensate for this longer research process. Graduate students, who generally have to make do with extremely tight budgets, will be especially hard hit.

To compensate for shorter research trips, historians will undoubtedly seek technological solutions. The advent of the digital camera has already revolutionized research. Using a digital camera allows a researcher to photograph literally thousands of documents in a single day. Though many historians continue to do research the old-fashioned way—taking notes—they might now pick up a digital camera instead. This move could change how the profession trains graduate students in the methodology of historical research.

Closely related to this issue is the possibility that the pandemic might also push R1 history departments to move away from requiring faculty to publish books in order to receive promotion and tenure. Publishing articles, which is the standard in social sciences such as economics and sociology, may become the norm. Writing a history book often involves traveling to many archives, some of them distant from the scholar’s home base. The process can take years. However, articles can be written in much less time and without as much archival research. Diminished research budgets and the health risks associated with extended travel could persuade history departments to accept articles for promotion and tenure in place of the traditional monograph.

The pandemic will almost certainly accelerate some trends that are already underway. The number of students majoring in history has been declining for years. Majoring in history in a more uncertain economic environment might be seen as an unaffordable luxury for all but the wealthy. Rather than follow their academic passion, students may instead pursue majors that appear to provide better job prospects. The STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) will probably be one of the main beneficiaries of this shift away from the humanities.

To survive this trend, history departments may redirect their scholarly emphasis. Rather than focusing on more traditional courses, we could see departments offering more courses on subjects such as the history of medicine and disease in order to remain “relevant.” History departments might also offer fewer courses in the realm of public history (oral history, archival studies, conservation, historic preservation, digital humanities), even though that is how historical records are preserved. The institutions that hire public historians, such as archives and museums, are suffering financially in the current time of upheaval, so they may be doing less hiring in the future.

History departments might also rethink their opposition to military history and diplomatic history. Both fields are seen as bastions of great man history, which has long been reviled in academic circles. Despite these criticisms, they remain a big draw for students. Another reason history departments might welcome more emphasis on military and diplomatic history is that the resurgence of nationalism makes expertise in these areas more relevant than at the peak of the trend toward globalization. History departments may lean in a more “practical” direction to satisfy the demand for relevancy and decide to offer more courses in these fields.

Other potential changes will affect all of higher education, but historians specifically will need to think about them. Teaching has already changed, at least in the short term. Professors are on campus less often than in pre-pandemic times. Historians may prefer to teach and meet students virtually rather than be on campus and risk becoming infected. To mitigate such concerns, campuses will undergo physical changes. Any new classrooms built will be larger in order to accommodate the same number of students, allowing students and professors to practice social distancing.

Departments will also have to alter their standards for evaluating the effectiveness of teaching. The migration from traditional face-to-face teaching to online instruction due to the pandemic will likely push departments to make virtual courses part of their permanent offerings. Yet remote learning is significantly different from the face-to-face learning experience. Teaching evaluations will have to change to account for this difference. On a related note, departments would be wise to offer their faculty and graduate students formal and informal courses on the best online learning practices.

Many colleges and universities depend heavily on room and board and tuition to fund operations. But the pandemic is already causing fewer students to live on campus, and as a result they (and their parents) are demanding lower tuition rates. This will mean less money for many academic departments. History departments will have to figure out how to avoid draconian budget cuts. The main beneficiaries of the competition for funds will undoubtedly be the STEM-related fields, which have already gained in popularity and influence. Public and private sector entities have for years been redirecting funds from the humanities to STEM. Moreover, because graduates in these fields command much higher salaries than those in the humanities, parents prefer that their children major in STEM-related fields— no doubt as a hedge against an uncertain economic future.

Changes in higher education precipitated by the pandemic could have a significant impact on the number of people who are actually working as historians and doing historical research. Professors who fall into one (or more than one) risk group might take early retirement, and universities might be inclined to go along with them, given declining enrollments. This could open the door for younger scholars to join the professorial ranks. However, because universities have been relying more heavily on adjuncts, new PhDs may not be offered a tenure track position when they are hired. The long-term decline in tenure hires is accelerating due to COVID-19.

Academic departments will not be the only campus institutions to experience cuts; libraries will as well. Building collections in specific areas is already difficult. This will become much harder in the immediate future.

Although recent racial unrest has prompted some history departments to offer more courses on African American history, ironically college campuses could become racially less diverse. The disproportionate impact of COVID on African American communities may also mean it disrupts college plans more for Black than for other students. Some Black students may think twice about going to college, at least in the near term. And if they do go, they might decide to attend HBCUs, which are less expensive and can often provide a more nurturing cultural environment. Offering courses on African American history, slavery, and colonialism to classes that are overwhelmingly white will provide awkward visuals for history departments attempting to position themselves at the forefront of diversity and inclusion efforts.

There will almost certainly be less immigration in a pandemic environment. Most wealthy nations have been limiting immigration for years, and the COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced this trend. It’s virtually certain that fewer foreign scholars will be visiting the United States. International programs, which exist on most university campuses, will find fewer students who can or want to travel overseas. Continuing education programs designed for senior citizens, which many history departments take part in, could become a thing of the past. College and university campuses will probably be much less diverse environments in the future.

There is no doubt that the longer the pandemic persists, the more probable it is that changes will occur and that some of them will be permanent. Historians need to prepare for these coming changes as much as anyone else. The longer they wait, the harder they will find it to adapt to change.