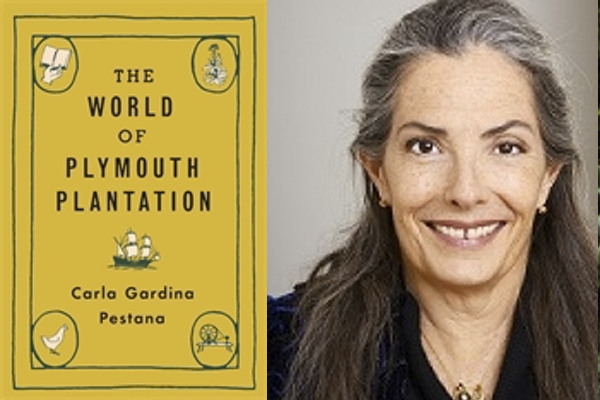

UCLA Historian Carla Pestana Debunks Myths About the Pilgrims and the Plymouth Colony

In the traditional view of the Pilgrims, one told in many 20th century textbooks, the Pilgrims came to Massachusetts on the Mayflower to make a break with old England and start a unique society.

In her new book, The World of the Plymouth Plantation, Dr. Carla Gardina Pestana corrects the “false impression that Plymouth was disconnected from the world that gave rise to it.”

In fact, the Plymouth settlers were “deeply connected” to many other places through England’s transatlantic trading network. They envisioned creating an English “plantation,” and carried with them many traditional English customs. The term “Pilgrims” was bestowed upon them in the 1700s in order to distinguish them from other settlers, particularly the Puritans of Boston.

Dr. Pestana, the Joyce Appleby Endowed Chair of America in the World in UCLA’s History Department, is the author of four previous books including The English Atlantic in an Age of Revolution, 1640-1661.

Pestana discussed her work with the History News Network.

Q. While we may think of Thanksgiving as a uniquely American holiday, you describe the gathering that took place in November 1620 as one that “invoked the seasonal festivals of English rural culture.” The event was not labeled “thanksgiving” until the 1800s. What shaped our modern conception?

Edward Winslow supplied a brief description of this gathering, the only mention we have of it. His account makes clear that the event marked the first harvest with a meal enjoyed in a community gathering. The martial display that kicks off the event may have attracted the 90 warriors whom Winslow mentions as showing up, but in the end, they supplied venison and took part in the feast. To mark a harvest with a community festival was a standard celebration in any English village, and, from what Winslow describes, that sort of event was their model. It occurred probably in September, a more appropriate time for a harvest gathering in New England, and it represented a chance to rest and celebrate after the hard work of bringing in the crops. The women who prepared the food did not experience a rest from their labors, however, which is usually true of most American thanksgiving celebrations to this day.

The label “Thanksgiving” got added later, and it invoked a different colonial practice, getting it slightly wrong too. In colonial New England, in later years, days of Thanksgiving occurred irregularly, prompted by specific occurrences. Local leaders called for such a day when they wanted to thank God for some good turn of events. A successful harvest could prompt such a day, but so did many other occasions: good news about events in England, success in war, a possible calamity (such as a fire) averted.

Thanksgiving days had a counterpart in days of humiliation. When events went against the community, leaders called for such an occasion, in which fasting and prayer brought everyone together, to beg God for forgiveness. They saw communal suffering as judgement for past sins and successes as a reward or a mercy. In this providential world view—in which God was thought to take a regular interest in the community’s affairs—New Englanders (and Christians elsewhere) responded to what it perceived to be the message behind each major change in their fortunes.

Thanksgiving as a national holiday denoted, at the time of its 19th century beginnings, hard work, sacrifice for the common good, and what we would call family values. Abraham Lincoln wanted to emphasize these values at the height of the Civil War, and they remain central to the holiday’s image. If today we have gotten far from a harvest festival and farther still from that of a one-off moment to thank God for a specific event, family remains at its heart.

Q. You write that the Plymouth settlers considered themselves “planters” intent upon “transplanting the society they knew as well as well as the household work regimens that made it possible.” For many Americans, “plantation” invokes images of southern aristocrats lording over enslaved workers.

The idea of plantation today means a large-scale agricultural undertaking that used enslaved laborers and (usually) produced a single crop like sugar, tobacco, or cotton. Planters were individual landowners who privately owned both the plantation itself and the slaves who worked it. Plantation is thus associated with the worst abuses of racial slavery, and activists today are understandably interested in eliminating that language.

Yet those who named Plymouth a plantation (or for that matter the recently renamed Rhode Island) were not thinking of slavery. Rather, they understood plantation to mean transplanting English people, their culture and ways of organizing society, into another location. It was, in other words, a synonym for colony or settlement, using a then-common meaning for the term. Ireland had plantations dating from the 16th century, created when lands seized from Irish landowners were turned over to English (or later Scottish) migrants who supported the English conquest of the island. In both the Irish case and the North American one, plantations introduced what we would today call settler colonialism, with the goal of displacing native peoples and replacing them with transplants.

That idea of plantation contained a certain arrogance, as those who did the planting clearly believed they had some right to occupy the lands of others. While it was not blameless, it was not worthy of censure for what modern critics of the term believe.

Q. The Mayflower Compact is often cited as the “birth of American democracy,” but you believe the men who wrote it in 1620 had another purpose in mind.

The men who signed the compact (which they did not call the Mayflower Compact) did so because they found themselves unexpectedly in a place with no government. They had hoped to land in what was then northern Virginia (around modern-day Delaware). Had they been there, they would have come under the jurisdiction of the Virginia Company. In the unhappy event of landing in New England, they decided they needed to curb an impulse toward anarchy that some leaders feared would overtake them. The document they drafted placed the group firmly under the authority of the English monarch, King James I. They agreed to create their own laws and ordnances, and pledged everyone’s “Submission and Obedience.”

The signers considered it a stop-gap measure until they could arrange a better basis for government, in particular a charter from the king. They never attained that charter, and they had to fall back on a ragged collection of inadequate documents, including a land grant from a defunct company and their shipboard agreement. Far from celebrating democracy, the agreement aimed to suppress individual impulses, granting more duties than rights. The document opens with allegiance to the king and ends with promising that they would submit and obey because those were its main concerns.

Q. You are skeptical that the “Plymouth Rock” memorialized in contemporary Plymouth Massachusetts was ever used as a docking point for the Mayflower passengers.

Plymouth Rock was identified as the possible landing site more than a century after 1620, when a group of interested townsmen took an elderly man out to the beach to question him about what he knew. If anyone had earlier worried about the precise landing site or discussed it, we have no evidence that was the case. There is little reason to believe that the elderly man (who could not have been an eyewitness) knew anything about the matter. Once he spoke, however, the townsmen dubbed the rock the landing site.

In a surreal twist, they then dragged this random boulder around, breaking it in the process, and installing it in various locations in town. It came to its final resting place, in the classical temple by the highway, much later, and that site was not its original resting place. So, the boulder that is supposed to denote the landing site is not at its original site nor is it likely to have had anything directly to do with the landing in any case.

A boulder as a landing site—often depicted as a sort of natural dock in various later images—makes no sense. Wooden boats steer away from boulders, not toward them. In addition, we have descriptions of the passengers wadding through the surf, dampening their clothing, when they disembarked. Clearly the sailors knew better than to deposit them on boulders, and the idea that they had done so may have been fueled by drink. I envision those who dragged the boulder around and broke as being the worse for having imbibed, in a sort of early version of a fraternity prank.