Will the Supreme Court Uphold the NCAA's Version of Amateurism?

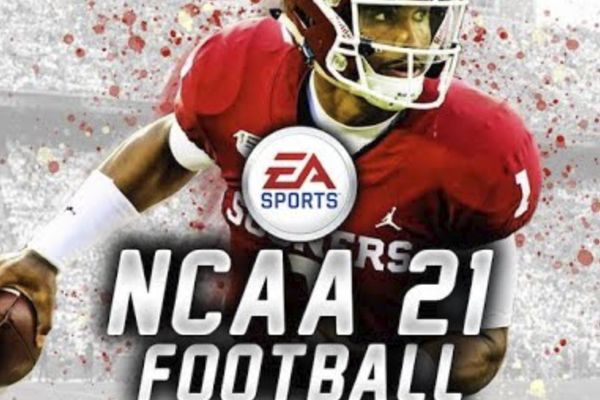

EA Sports has, to the chagrin of many gamers, not produced an NCAA-licensed football video game since 2013. The video game market is just one area of dispute over the right of collegiate athletes to compensation for the commercial use of their names, images, or likenesses (NIL). Image Sports Gamers Online.

On March 31, 2021, the U. S. Supreme Court will hear the case of NCAA v. Alston. It is an antitrust case in which the NCAA argues that the property rights of Division I basketball and FBS football athletes should be dismissed because college athletes are amateurs. If the NCAA wins, college athletes will continue to be deprived of financial benefit from the commercial use of their names, images, and likenesses (NILs). The NCAA argues that it must control what players are paid to protect their amateurism. Shawn Alston, as part of a class action suit, argues that the NCAA is violating antitrust law, and that property rights belong to the athletes as they do for all other college students, and they should be able to profit from their use.

As I have just completed a book, The Myth of the Amateur: A History of College Athletic Scholarships (University of Texas Press, 2021), I decided to initiate an amicus brief for the U. S. Supreme Court, challenging the NCAA’s perpetuation of the myth of college amateurism. I asked five other historians who have written on the history of intercollegiate athletics to join me in the amicus brief. Taylor Branch wrote a piece in the Atlantic Monthly (October 2011) about the exploitation of college athletes under NCAA rules. He is better known for the Pulitzer Prize he won for Parting the Waters, the first book in his trilogy on Martin Luther King. Richard Crepeau is a historian at the University of Central Florida, who has written on Roman Catholic athletes as well as a recent history of the National Football League. Sarah Fields, a lawyer and historian at the University of Colorado, Denver, has written a book about female competitors in contact sports and one on sports celebrity and the law. Jay Smith is a French history scholar at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, but has written on the decades-long disgrace of the notorious athletic-academic scandal at his institution. John Thelin is a prominent educational historian at the University of Kentucky, who wrote a history of college athletic reform attempts.

I was a history major and a baseball and basketball player at Northwestern University decades ago and was given a scholastic scholarship, but I was told if I did not keep a “B” average it would turn into an athletic scholarship. I was not good enough to profit from my NIL, nor did anyone on my teams know that it was possible. Later I did my doctoral work at the University of Wisconsin, writing my dissertation on an athletic conference. I then joined the Penn State University faculty shortly after Joe Paterno became head football coach. I have been interested in how athletes have been paid, not only when I was an undergraduate, but when I began researching intercollegiate athletics. That took me back to the original college contest in America. It took place in 1852, nine years before the Civil War. It occurred because a railroad magnate wanted to make money from sponsoring a crew meet between Harvard and Yale. He told the Yale captain that if he would get Harvard athletes to agree, he would pay all expenses for an eight-day vacation for the crews at New Hampshire’s largest lake, Lake Winnipesaukee. From that time to the present, athletes have often been paid in one form or another.

Today, a major question is the paying of athletes for their property rights to use their names, images, and likenesses. The U. S. Supreme Court will soon be pondering the question of whether the NCAA denying such property rights to athletes is a horizontal antitrust violation under the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. The issue should have come up first in the early twentieth century, more than a century ago. Probably the most prominent player among the big-time football schools of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton was James Hogan, a 29-year old who was paid in a variety of ways. He had his tuition paid, lived in the most luxurious of Yale’s dormitories, ate free meals at the University Club, profited on scorecard sales at Yale baseball games, and was given a vacation in Cuba when the season was over. But more important to the Supreme Court case, Hogan profited from his name and image from every American Tobacco Company pack of “Hogan” cigarettes sold in New Haven. It was legal then to profit from his NIL.

The U. S. Supreme Court will hear of the many ways that big-time college athletes are paid in 2021. That is, there are more than a dozen methods in which athletes are paid legally beyond a full athletic scholarship, but which don’t violate “amateurism” under NCAA rules. For instance, Olympic swimming gold medalist Katie Ledecky was awarded more than $300,000 in the last Olympics, and she remained eligible to swim for Stanford University. An international gold medal swimmer, Joseph Schooling of Singapore, was given $700,000 for beating Michael Phelps in the 100-meter butterfly. He then swam for the University of Texas as an amateur. The NCAA also allows athletes to draw thousands of dollars from two multi-million dollar funds, the Student Assistance Fund and the Academic Enhancement Fund. In addition, federal Pell Grants for needy athletes increase athletes’ funding. The NCAA also allows money to go to the conference athlete of the year, a team’s most-improved or most valuable player, and for bowl bound or March Madness player freebies worth hundreds of dollars. This is not amateurism that the NCAA claims it is protecting. Yet, the NCAA opposes a player gaining a portion of the revenue made from game jerseys sold which display his or her name and number (or from video games licensed by the NCAA). That property right is off limits, and a player who seeks to capitalize on it will be classified as a professional and lose eligibility.

Our amicus brief points out the NCAA’s hypocrisy by quoting Taylor Branch: “no legal definition of amateur exists, and any attempt to create one in enforceable law would expose its repulsive and unconstitutional nature.” According to Branch, “without logic or practicality or fairness to support amateurism, the NCAA’s final retreat is to sentiment.” Historically, we point out the false NCAA claim that amateurism is central to college sport. NCAA amateurism, originally opposed to any athlete being paid in any form, has been modified so drastically that athletes can now be paid in a variety of ways. What sets college athletic participation apart from “professional” sports is not that intercollegiate sports are amateur, but that they are part of institutions of higher education. College sports are, at least nominally, intended to be educational, while professional sports are not. Before a decision is made in the NCAA v. Alston case, the Supreme Court justices should read a brilliant article in the Harvard Law Review published three decades ago. “Judicial invalidation of the amateurism principle,” the legal experts stated, “may actually allow the NCAA to place more emphasis on academic values in its members’ sports program.” Six knowledgeable historians agree.