Historically, Black Distrust of Police is About More than Acts of Violence

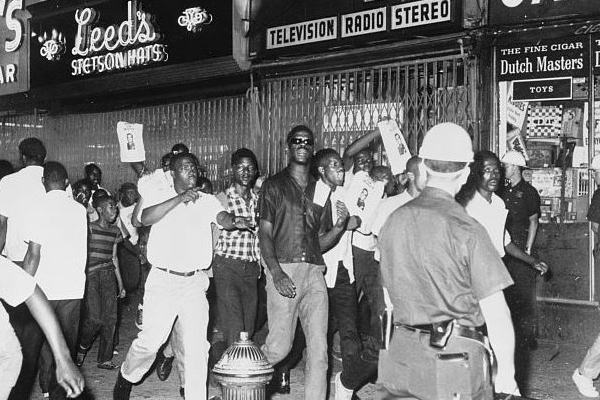

Protesters on 125th Street carry posters of NYPD Lt. Thomas Gilligan, who was not indicted after killing 15 year old James Powell in 1964.

Police accounts claimed Powell was armed with a knife, an account believed by few Harlem residents.

We’re supposed to be living in a time of racial reckoning. After the world watched George Floyd’s excruciating street execution, over and over, there emerged a groundswell of support for antiracist work throughout society in the spring and summer of 2020. Reforming policing and reining in its obvious excesses became one of the most immediate goals.

In the last place that George Floyd called home, a majority of Minneapolis City Council members initially pledged, loudly, to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department, which turned into a modest budget cut. Disappointed activists put the question of replacing the police department with a department of public safety to voters this Election Day, and it failed. A yearlong, bipartisan police reform effort in Congress collapsed, producing nothing at all. Various states and localities have implemented reforms, such as limiting chokeholds or making police complaints publicly available, almost singularly focused on reducing violence and death at the hands of police.

This makes perfect sense, especially given the prevalence of these deaths caught on video in recent years, and the stark horror of watching people lose their lives, often in circumstances that are questionable, at best. However, policing’s racial problem is age-old, and goes well beyond physical violence as I document in my new study of structural racism in New York in the 1950s and 1960s, The Harlem Uprising - Segregation and Inequality in Postwar New York City. If we don’t understand the history, we miss the long legacy of distrust that people of color, particularly Black people, feel toward the police. And beginning and ending at beatings and shootings leaves us with a severely incomplete understanding of what is and has been wrong.

In July, a white NYPD lieutenant, with nearly two decades on the job and well over a dozen commendations for outstanding police work, including four for disarming men with guns, shot and killed a fifteen-year-old Black boy. He said the youngster came at him with a knife, even when the officer announced himself, even after he shot the boy the first time. Witnesses disputed the officer’s account, and there was no video. A grand jury declined to indict the lieutenant, and the department ruled the shooting justified.

You may have heard about this one, but probably not, because it was in 1964. The boy was James Powell, Thomas Gilligan his killer. As for who believed this story, the New York Amsterdam News, the city’s oldest Black newspaper wrote that “Nobody in Harlem does.” In 1964, that was understood to mean Black New Yorkers did not trust the NYPD’s version of events. They had little reason to.

The NYPD in the mid-1960s was thoroughly corrupt, racist and violent. Officers, individually and collectively, reserved their worst behavior for the city’s segregated Black neighborhoods, like Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant and Brownsville. Taking bribes from building contractors, tow truck drivers, funeral directors and defense lawyers was as much a part of the job as clocking in. They ran protection rackets on sex traffickers and heroin dealers, generating substantial weekly payments that would be split among the men working these patrols, and required local businesses to pay smaller amounts, which would be divvied up and spread around the local precinct. To anyone skeptical, read the Knapp Commission’s report.

Police in the city treated Black neighborhoods, especially Harlem, as crime reservations, containment areas for drugs, gambling and sex work. It’s not that the NYPD, from rank-and-file high up into the executive corps, permitted these illicit industries to exist. Instead, they worked hard to make sure these outlets of misery and ruin flourished, both out of selfish financial motives and racial spite, given that the NYPD was 95 percent white. Multiple memoirs from men on the force during this time establish that they worked with “a deep sea of racism and bitterness, poison and untamed cruelty in our souls.”

And yes, the police were also violent, ranging from arbitrary roughness on the street, to sadistic squad room beatings, to shootings. Of course Black New Yorkers opposed this. But they also wanted safer communities, which the NYPD assiduously denied them. They had to live with all manner of random street crime, especially that which is concomitant with an impoverished neighborhood rife with addiction. More policing and less police violence and discourtesy are not mutually exclusive, or at least they should not be.

Some of this behavior has changed. It is much more difficult for police departments today to be so outwardly corrupt that they effectively act as untouchable criminal organizations. But many aspects remain. Police departments across the country have long used drivers as ATMs to fund local budgets, frequently targeting Black motorists for heightened enforcement of minor traffic laws. Not only do these stops engender bitterness, but the resulting fines also threaten to financially ruin people already living on the edge, and too often escalate into totally unnecessary shows of force. Ticket and arrest quotas demand that people be brought into the criminal justice system without good reason.

The racist assumption that Black and Brown men are more likely to be up to no good led to the explosion of stop-and-frisk in New York City, a practice the state approved in 1965. For decades, the police practiced the on-street search of someone who aroused an officer’s suspicion, including “furtive movements” or simply being in a location with a high crime rate. The number of these searches peaked at 685,724 in 2011. Since 2014, the department instructed officers to only detain people when they have a strong suspicion of criminal activity, and the numbers dropped into the five-figure range.

For the last two decades, ninety percent of those officers detained were Black or Latinx, though the city is about 45 percent white. Ninety percent were released, having been found not engaging in or possessing anything illegal. Put another way, the NYPD was stopping and frisking tens of to hundreds of thousands of people, every year, who were doing nothing illegal. There is no evidence the practice measurably reduces crime.

The police also lie, from the smallest to the direst of matters, and courts side disproportionately with an officer’s word. Officer Michael Slager of North Charleston, South Carolina, said he feared for his life because Walter Scott had taken his Taser and Slager “felt threatened.” In reality, Slager had tased Scott after a physical altercation; Scott then ran away, unarmed, and Slager shot him in the back five times, killing him. But again, this is just a recent example of a very old practice, and perhaps one of the worst examples of a “cover charge,” or a false accusation after the fact that permits officers to brutalize and arrest or kill someone. If the victim survives and complains, who believes an alleged felon?

Policing has been in need of reform since its inception. Changes have come, but they’ve been slow, and significant numbers of people, disproportionately Black and Brown, have experienced and continue to experience discourtesy, bigotry, false allegations, and violence. The outrage we saw explode in 2020 shouldn’t have surprised anyone. If anything, we should be surprised the streets of America had been so quiet before.

People of color, and Black people in particular, have always experienced justice differently in this country. Distrust toward the police is multigenerational, and not the result of one violent act, or Marxist agitation, or exposure to rap lyrics. Until we fundamentally reimagine what policing looks like in this country, this situation seems unlikely to change.