Malverne: The Incomplete Struggle for School Integration on Long Island

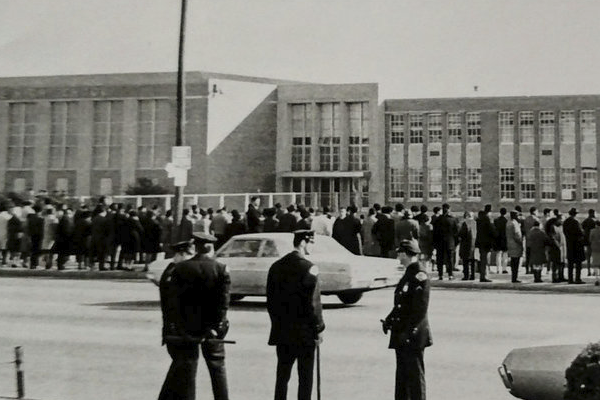

Local residents protest the proposed integration of Malverne High School, c. 1963. Photo courtesy Malverne Historical and Preservation Society

The 1960s struggle to racially integrate the Malverne, New York school district was revisited by CBS News as part of its Black History Month reporting. Malverne schools were recently in the news again because high school students are demanding that the name of a street in town be changed because it is named after Paul Lindner, a local real estate developer, who was Grand Kleagle of the Nassau County chapter of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s and a leading state-level Klan official.

There are moments in time when the twists and turns of history open up new possibilities. The 1960s struggle for a more racially integrated society in the United States and in Malverne was one of those moments. Today we live with the political and social consequences of our failure to achieve a more just society sixty years ago.

The demographics of the Malverne school district and of Nassau and Suffolk Counties on Long Island made Malverne one of the few areas where a model school integration plan could be implemented. Long Island’s two suburban counties are a checkerboard of 124 small, racially, ethnically, and economically segregated school districts. Part of the problem was the way the New York metropolitan area suburbs sprouted up after World War II and part of the problem was intentional segregation. Before the war, most of Long Island was farmland with a scattering of small towns and some vacation estates for the wealthy. Essentially rural school district boundaries corresponded to local communities. With the mushrooming of suburban development on Long Island neighboring towns that had been separate now ran into each other, but the old school boundary lines remained. Meanwhile home values often depended on school performance and demographics, while local taxes based on home values funded schools, all factors that contributed to school segregation and inequality.

But a big factor was redlining. After World War II, veterans were entitled to government insurance for home mortgages, but the mortgages had to be issued by local banks. Banks and real estate brokers conspired to keep neighborhoods and schools racially segregated. Black families could move into communities which banks and realtors already considered devalued (and sometimes marked in red on maps), but they were not shown homes or issued mortgages in other locales.

The town of Malverne is still divided between two school districts, with areas of Malverne south of Franklin Avenue or west of Cornwell Avenue feeding into neighboring Franklin Square schools including grades 7-12 at Valley Stream North High School. Cross-district school integration on Long island has always faced too much parental and political opposition, but the Malverne school district was in a unique position on Long island because it included two different neighboring communities, Malverne and Lakeview.

Lakeview was an area to which Black families were largely consigned by redlining and other restrictive practices after World War II, so the community’s school age children were largely African American. Today the population of Lakeview remains about 85% African American.

The campaign to racially integrate Malverne school district schools began in earnest in September 1963. Pro-integration families boycotted the Malverne public schools and temporary "Freedom Schools" schools were set up in community churches and at the Jewish Center. White parents opposed to a school integration plan secured support from State Senator Norman Lent, who unsuccessfully introduced two bills in the state legislature outlawing the busing of students to achieve racial balance and the assignment of pupils to schools based of race, color, religion or national origin.

When initial efforts were made to reassign students to racially integrated elementary schools in 1965, a large group of white families demanding the maintenance of “neighborhood schools” boycotted the district’s schools and set up their own independent classes for their children. As a compromise, in August 1967 the Malverne School Board and the State Education Department finally agreed on a new “4-4-4" plan. Students were divided between two kindergarten through 4th grade schools and then assigned to a district-wide middle school and high school.

In many ways, the final plan to racially integrate Malverne schools was doomed from the start. Intense white opposition to school integration plans, including picket lines, school boycotts, and lobbying in Albany, led to white flight from the Malverne public schools and the gradual resegregation we see today.

According to the 2020 United States Census, the population of Malverne is 78% white, 5% Black, 5% Asian, and 8% Latino. Neighboring Lakeview is 79% Black, 8% white, and 6% Asian. Lakeview and part of Malverne feed into the Malverne school district. Eighty-two percent of the students attending school in the Malverne Union Free School District are members of minority groups. The student population at Valley Stream North High School in Franklin Square, where many Malverne students are zoned remains interracial, but with a declining white minority. Meanwhile, the student population at the Our Lady of Lourdes, a pre-K through grade 8 Roman Catholic school in Malverne is 85% white. The student population at Chaminade, a nearby all-boys Roman Catholic high school is 90% white.

In an era when school reform and budget savings are championed by representatives of both major political parties, Long Island cannot economically, politically, or culturally afford to maintain small racially segregated school districts. Malverne schools and schools in surrounding communities do not have to be racially segregated. In nearby Rockville Centre, 80% of the students are White. If Malverne, Lakeview, and Rockville Centre were combined into one school district, the student population would be 53% White, 30% Black, 13% Latino, and 4% Asian. If we think even more broadly and Malverne, Lakeview, Rockville Centre, West Hempstead, Lynbrook, and East Rockaway were consolidated into a manageably sized district with under eleven thousand students, the student population would be 69% White, 14% Black, 13% Hispanic, and 4% Asian.

Long Island’s diversity is one of region’s greatest resources. It is long past time to racially integrate its schools.