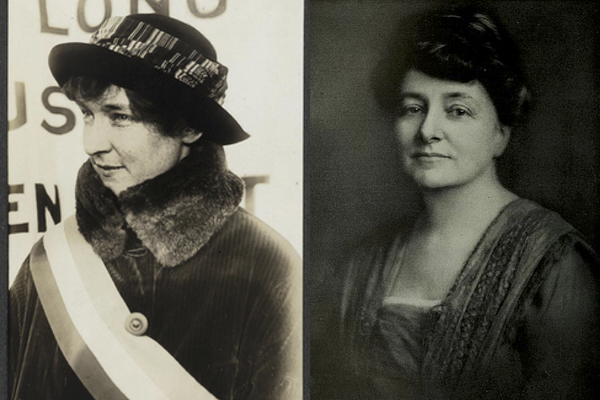

A Tale of Two Suffragists: Hazel Hunkins and Maud Wood Park

Two suffragists arrived in Washington, D.C. in late 1916, one from Billings, Montana and the other from Boston. Born twenty years apart, they spent the next three years in the nation’s capital working for the same goal by radically different means. If by chance their paths had crossed, they probably would have not have spoken to each other, so deeply did they identify with the strategies of their rival organizations. But they were equally passionate about winning the vote.

Hazel Hunkins was the younger of the pair. Born in 1890 in Colorado but raised in Montana, she was a proud graduate of Vassar who was frustrated when she couldn’t pursue a career in chemistry. Temporarily living at home, she met a field organizer for the upstart National Woman’s Party (NWP), which Alice Paul had just founded to push for a federal suffrage amendment. Hunkins became an instant convert to the feminist cause. After crisscrossing the West as a paid organizer for the NWP, she moved to Washington to oversee its organizers in the field. When Alice Paul sent out “Silent Sentinels” to picket the White House in January 1917, Hazel Hunkins was one of the most stalwart volunteers. She was twenty-six years old.

Maud Wood Park would never have done anything as radical as picketing the White House but her commitment to women’s suffrage was just as firm. An 1898 graduate of Radcliffe College, she was recruited to join the suffrage movement in college by Alice Stone Blackwell, the only child of Lucy Stone, whose 1855 refusal to take her husband’s name in marriage spawned the term “Lucy Stoners.” Temperamentally committed to working within the system, Park served on the executive board of the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association, and she helped found the Boston Equal Suffrage Association for Good Government and the College Equal Suffrage League. In 1916 Carrie Chapman Catt recruited her to come to Washington to become the chief lobbyist of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the oldest and largest mainstream suffrage organization in the country.

The Congressional Committee that Maud Wood Park soon headed earned the nickname “Front Door Lobby” because, in the words of one journalist, they “never used backstairs methods.” She methodically kept tabs on the 96 senators and 435 members of the House of Representatives who held the fate of the Nineteenth Amendment in their hands. This lobbying lacked the glamour and excitement of marching in a suffrage parade or participating in an open-air meeting, but it was absolutely crucial to the ultimate success of the movement. In January 1918, the House passed the so-called Susan B. Anthony Amendment but the Senate would not follow suit until June 4, 1919. Neither victory would have happened without the deliberate and scrupulously non-partisan efforts of Maud Wood Park.

Hazel Hunkins chose a different path even if she was after the same goal: she turned to militant action to force Woodrow Wilson and other elected officials to support the federal amendment. Hunkins was arrested on at least three occasions, mainly on trumped up charges of disorderly conduct or obstructing traffic. When she was imprisoned after protesting at Lafayette Square, across from the White House, Hunkins and her fellow suffragists immediately embarked on a hunger strike to highlight the terrible conditions at the local jail. Weakened not just by hunger but by contaminated water, the suffragists were released after five days. Hunkins went home in an ambulance. She was arrested one more time in January 1919 for burning Woodrow Wilson’s speeches in “watchfires for freedom” across from the White House. That was her last militant act.

There was no love lost between the rival wings of the suffrage movement, but it is too simplistic to reduce the clash between the NWP and NAWSA to a generational dispute between brash youngsters committed to militancy and “old fogeys” dedicated to working within the system. In the final decades of suffrage activism, younger women flocked to NAWSA, swelling its ranks with new recruits. And even though the NWP styled itself as “the young are at the gates,” one of the first pickets to be arrested was Lavinia Dock, who was almost sixty years old. Dock spent a total of forty-three days in jail for the cause.

Despite their deep-seated differences over tactics and strategy, there were some surprising commonalities between the two groups. The most striking was how both wings of the suffrage movement provided a welcoming space for a range of living and working arrangements that definitely fell outside the bounds of heteronormativity. At the height of her suffrage militancy, Hunkins began an affair with a married man whose wife refused to give him a divorce. Undaunted, the couple moved to England in 1920, where they had four children before finally marrying in 1930. Maud Wood Park married an architect while she was a student at Radcliffe, but she kept that marriage secret so as not to interfere with her studies. When she was widowed, she kept her second marriage secret as well, reasoning that her career would be taken more seriously if she wasn’t suspected of neglecting her husband. The deeper we dig, the more examples we find of suffragists young and old leading far more unconventional lives than their somewhat dour public reputations might suggest.

Both Hazel Hunkins and Maud Wood Park enjoyed significant careers after the Nineteenth Amendment was passed. Park served as the first president of the National League of Women Voters and later was instrumental in the establishment of the Woman’s Rights Collection at Radcliffe in the 1940s. Hazel Hunkins-Hallinan (as she was now known) joined the Six Point Group, the leading British feminist organization, and served as its chair in the 1950s and 1960s. After speaking at Alice Paul’s memorial service in 1977, she took part in a march in support of the Equal Rights Amendment organized by the National Organization for Women. Once a feminist, always a feminist.

Thousands of women took different paths and pursued multiple strategies to win the goal of securing the right to vote. Their individual acts of courage and persistence, their quiet determination and flashes of militancy put human faces on the collective drama of social change. As we count down to the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, these personal stories remind us that the road to women’s full participation in public life has been a long and contested one, sometimes even pitting women against each other as they fought for the goal of equality. The women’s suffrage movement was stronger because of this diversity of approaches. The split may even have hastened its ultimate success.