A History of Why Trump Abandoned the Kurds

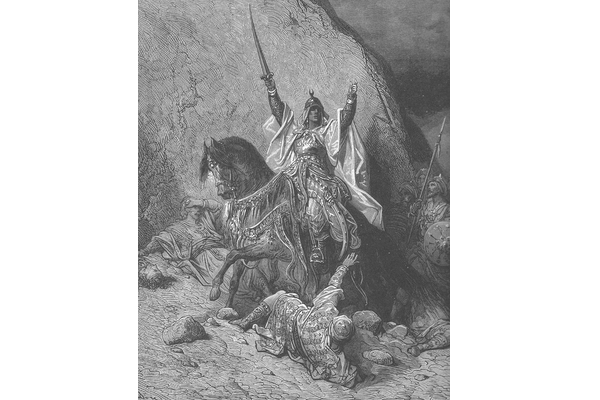

An-Nasir Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub/ Saladin

Perdition’s antechamber is the circle known as Limbo, and according to poet Dante Alighieri in the fourteenth-century, this bucolic place was for the repose of those righteous pagans who lived before the incarnation of Christ. While the Jewish prophets and patriarchs had been liberated by Christ after his crucifixion, the pre-Christian pagans who lived righteously were forever to dwell in this not-quite-heaven. Dante makes a temporal exception however, allowing a few Muslims who were born after Christ’s life. Perhaps the most surprising of these inclusions is a general who defeated the Christian monarch Richard I during the Third Crusade of the twelfth-century.To honor this Islamic military genius was as close to ecumenicism as was possible for Dante. Because of his qualities of virtue, charity, chivalry, and equanimity, the general appeared in Canto IV with just a single line: “And sole apart retired, the Soldan fierce.”

An-Nasir Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub has long been known to Europeans as Saladin. Religious studies scholar Karen Armstrong wrote in Holy War: The Crusades and Their Impact in Today’s World that “he was revered by both East and West and was the only Muslim hero to be given a Western version of his name by his admirers in Europe.” In victory, Saladin was not cruel but compassionate, not gloating but generous, not intolerant but humane. For centuries, these perceptions of Saladin’s character have also been imparted onto the people he was born amongst, a branch of the Indo-European linguistic tree speaking a language closely related to Persian. They were scattered across the Near East with significant populations in the countries that would become Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. The name of Saladin’s people are the Kurds.

With perhaps 45 million Kurds spread in a diaspora cross those nations, with small communities in Europe and North America, the Kurds are arguably alongside the Romani as one of the biggest groups of technically stateless people in the world. Largely secular Muslims, the Kurds are diverse in their faiths, including Sunni, Shia, and Sufi Muslims, Zoroastrians, Christians of a variety of denominations, and the indigenous religion of Yazidism that has connections to the Gnosticism of late antiquity. Frequently the targets of oppression in their host countries, the Kurds have been periodically marked for official persecution as nations have banned their language and folkways, and committed ethnic cleansing and genocide.

Like many indigenous peoples, the Kurds were the orphans of colonialism. By the provisions of the Treaty of Sèvres signed by the Allies at the conclusion of World War I, the Kurds were promised a homeland carved from the former confines of the Ottoman Empire. The provision was part of the same trend towards national self-determination embodied by the Balfour Declaration that ultimately lead to the establishment of Israel. Three years later, that promise was broken by the Treaty of Lausanne. As in Africa and Asia, Western colonial powers imposed arbitrary borders, dividing ethnic and linguistic groups from each other, with ramifications that reverberate today. The result was that the Kurd’s traditional homeland was distributed through several other countries, effectively nullifying (for a time) aspirations of Kurdish sovereignty. Historian Michael Eppel explains in A People Without a State: The Kurds from the Rise of Islam to the Dawn of Nationalism that the “populations of Kurdistan – the Kurds and Armenians – are the descendants of ancient residents of the area who mingled with the waves of conquerors and immigrants who settled there and became part of the population.” Both Armenians and Kurds, not coincidentally, suffered from Turkish aggression and Western indifference.

For the past century the Kurds have valiantly fought for the establishment of a state, free from Syrian, Iraqi, Iranian, or Turkish persecution. In those attempts they have often allied with Western powers, particularly the United States, but repeatedly they’ve been betrayed, as Europeans and Americans are content to let the Kurds wait in Limbo. With Donald Trump’s promise to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to withdraw American troops from northern Syria, tacitly condoning the subsequent Turkish invasion of what had been a Kurdish autonomous zone, the betrayal of our allies has reached a new nadir. Unlike past abandonments, this decision bears no strategic benefit to Washington (even as Vice President Mike Pence has ham-handedly tried to manage what seemed to be Trump’s impetuous writing of foreign policy on-the-fly). That’s without even mentioning the truly bizarre, infantile, and embarrassing letter Trump wrote to Erdoğan released by the White House.

Much has been written about the Kurds in the last two weeks following the United States’ abandonment of our of most loyal allies in the Middle East, but as Dante’s example proffers, the West has long been content to let the Kurds dwell in Limbo rather than Paradise; pleased to take their support when it’s useful and to turn their back when it becomes strategic to do so. This is why it’s so important to enumerate precisely the way in which the United States has frequently turned its back on the Kurds despite their loyalty. We must also consider the implications of Trump’s abandonment of them now – an action that as thoughtless as it might seem actually betrays more nefarious intentions than simply bolstering the president’s Istanbul real-estate portfolio.

In The Great Betrayal: How America Abandoned the Kurds and Lost the Middle East, international studies scholar David Phillips details the United States’ long disreputable history of abandoning our ally. While Trump’s recent perfidy is perhaps the most galling of disloyalties, Philips said that Washington has “betrayed the Kurds in Iraq by failing to support their goal of independence,” as various U.S. administrations saw more utility in placating Istanbul, Damascus, and Baghdad than honoring commitments to our ally. In 1975 the United States cut military funding to the Kurds, allowing Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein to attack; by the time of the Reagan administration, the U.S. looked the other way as Hussein, who was also embroiled in war against our adversary of Iran, launched chemical gas attacks against Kurdish civilians. By the first Gulf War, President George H.W. Bush implored the Kurds to rise up against Hussein, which they bravely did, only to have the United States abandon commitments and support which led to more slaughter.

More recently, the Kurds have been able to carve out a semi-autonomous Kurdistan in northern Syria, joining a previous Iraqi Kurdistan that was made possible by an Allied No-Fly Zone in the previous decades. Born out of the chaos of the Syrian Civil War, the Kurdish regions of that nation have been instrumental in the fight against, and the victory over, the theocratic and brutal Islamic State. Since ISIS has spread like a noxious gas across the Levant and the Near East, it has been Kurdish fighters, Kurdish blood, and Kurdish lives that reclaimed land inch by inch, mile by mile. This was a brutal war against a self-declared “Caliphate,” an existential struggle against a fundamentally fascistic form of fundamentalism.

Even in this we had a responsibility, as journalist James Verini describes in They Will Have to Die Now: Mosul and the Fall of the Caliphate, as Iraqis, Syrians, and Kurds were “living and dying in a new and blacker war, a war with a foe at whose core was a death cult… a war that nevertheless would not be happening, at least not in this way, if not for the American war that preceded it.” In fighting against ISIS, Kurdish paramilitaries (particularly their fearsome divisions of women fighters) have been the decisive factor in victory. Now that Trump has greenlit Erdoğan’s invasion, Turkey has already committed war-crimes against the Kurds, the region is destabilized, other reactionary forces such as Russian president Vladimir Putin have been empowered, and ISIS is resurgent.

There have been denunciations across a shockingly wide swath of the political spectrum. Among the Republicans, who despite Trump’s continued assaults on the Constitution remain steadfastly loyal to the aspiring authoritarian, there was a brief respite of sanity as figures like Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham criticized the move as fundamentally jeopardizing the national security of the United States. Writing in the Washington Post, McConnell called Trump’s decision a “strategic nightmare,” while evangelical power-broker Pat Robertson, recalling how the Kurds were instrumental in defending Christians from ISIS, said that the president’s actions had left him “absolutely appalled.” While it could be said that Republicans have never found a war that they didn’t like, the disgust at Trump’s betrayal has similarly angered virtually all major Democratic officials, with former Vice President and current presidential candidate Joe Biden’s contention that “Trump sold [the Kurds] out” is a representative example of sentiment.

Lest this be interpreted as the foreign policy wings of both parties simply doing what the foreign policy wings of both parties do, it’s worth considering that some of the most vociferous condemnations of our Syrian pullout actually come from the far-left. Writing for Jacobin, Djene Bajalan and Michael Brooks argue that an American promise to leave northern Syria “would not be a blow to U.S. imperialism,” but would rather provide opportunity for Turkey to “destroy [Kurdish] radical democratic dreams.” Few issues would seem to unite Pat Robertson and Jacobin, but it’s actually Bajalan and Brooks who explain the why of Trump’s betrayal. The Kurds’ were not simply allying in our fight against ISIS, for that was a pragmatic relationship born from military necessity, but they are also among the exponents and experimenters in one of the most radical and egalitarian political arrangements currently being enacted in the world, during an era when democratic values are seemingly on retreat.

In the Syrian region of Rojava, the Kurds haven’t been able to just win victory against ISIS, but they’ve also been able to construct a nascent state whose values are almost diametrically opposed to the Caliphate in every conceivable way. Based around the radical political thought of American philosopher Murray Bookchin and the theories of Kurdish Worker’s Party founder Abdullah Öcalan, Rojava has become a bulwark of progressive organization. Marcel Cartier writes in Serkeftin: An Account of the Rojava Revolution (the title means “Victory” in Kurdish) that in northern Syria there is “a feeling, a spirit, the life and soul of a revolution.” Among the Kurds there has been the establishment of a radical state committed to complete gender equality, to ecological stewardship, to multiethnic democracy, all organized around “Democratic Confederalism.” With authoritarianism ascendant from Moscow to Washington, Beijing to Brasilia, the example of the Kurds has become a beacon for those who fear the eclipse of democracy.

And that’s why Trump has abandoned the Kurds, not because of a hotel in Turkey, but because Rojava’s example has to be sacrificed in the modern day “Great Game” of alternating cooperation and competition between neo-colonial leaders in Turkey, Syria, Russia, and the United States. Trump’s disdain for the Kurds isn’t in spite of their establishment of direct democracy in Rojava, it’s because of it. The Kurds have become a cause among the international left, as the Spanish Civil War was during the 1930’s. Writing again in Jacobin, Rosa Burç and Fouad Oveisy argue that “Rojava, the site of a remarkable peoples’ revolution, is on the brink of colonization and extermination. The international left must stand against it.” That the Kurds are associated with socialism, anti-fascism, and radical democracy isn’t incidental to Trump’s abandonment of them – it’s the reason why he has. In that larger sense, such an abomination isn’t merely disloyalty to an individual group of people, it’s disloyalty to the very idea and promise of democracy. It’s worth remembering that when Dante designed his inferno, he placed traitors in the ninth and last circle, as far from noble Saladin as they could be.