How Will History Judge Trump’s Foreign Policy?

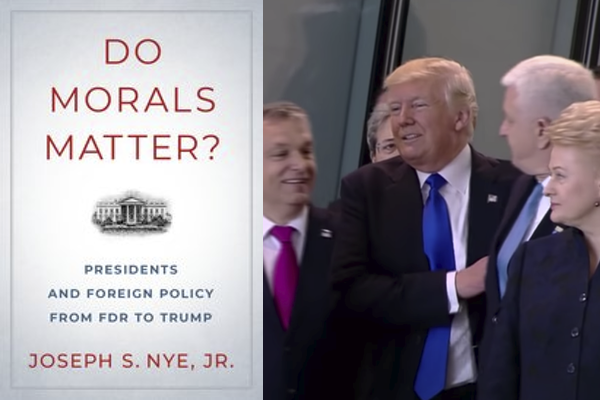

The 2020 election will likely turn on domestic politics, not foreign policy. This makes sense, as the COVID-19 outbreak and the Trump administration’s response to it have affected nearly all aspects of American life and pose a potential catastrophe. Yet, the pandemic is a global phenomenon. It has spread globally through travel and commerce, and Trump’s response reflects and shapes his views of America’s relationship to the rest of the world. Will Trump move American foreign policy in new directions? How will his decisions be rated by historians? As each day brings new news in an unsettled situation, it is difficult to answer those questions. But it is possible to place Trump in the context of other presidents in the age of American preeminence. My book Do Morals Matter? rates the 14 presidents since 1945 and gives Trump a formal grade of “incomplete,” but he ranks poorly because of his damage to the American led international order.

Prescriptive approaches to foreign policy vary considerably, but my book argues that the most effective and worthy presidencies were those that helped build a liberal international order. Before the end of World War II and his death in office, Franklin Roosevelt saw the mistakes of America’s isolationism in the 1930s. Conceiving the United Nations, FDR pointed his successor toward a liberal international order after 1945. A turning point was Harry Truman’s post-war decisions that led to permanent alliances that have lasted to this day. The US invested heavily in the Marshall Plan in 1948, created NATO in 1949, and led a United Nations coalition that fought in Korea in 1950, and in 1960, signed a new security treaty with Japan.

The period of American primacy after World War II has come to be called “the liberal international order,” although the term is somewhat misleading because the order was never global and not always very liberal. What emerged was a loose array of multilateral institutions where weaker countries were given institutional access to the exercise of American power, and the United States provided public goods and operated within a loose system of multilateral rules and institutions, including the UN, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Health Organization. It was a combination of Wilsonian liberalism and balance of power realism, and it had four major strands: security, economic aid, global commons, and liberal values.

American foreign policy has seen bitter divisions over military intervention in developing countries like Vietnam and Iraq, which revealed major challenges to the liberal order from Cold War anticommunism and neoconservatism. Nevertheless, the liberal institutional order enjoyed broad support until the 2016 election when Donald Trump became the first candidate of a major party to attack it. His populist appeal rested on the economic dislocations of globalization that were accentuated by the 2008 Great Recession, and cultural changes related to race, the role of women and gender identity that had polarized the American electorate. While he did not win a majority of votes, Trump successfully linked white resentment over the increasing visibility and influence of racial and ethnic minorities to foreign policy by blaming economic problems on bad trade deals and on immigrants competing for jobs. In January 2017, Martin Wolf wrote in The Financial Times “we are at the end of both an economic period – that of Western led globalization – and a geopolitical one, the post-cold war ‘unipolar moment’ of a US-led global order.” If so, Trump may prove to be transformational.

The current debate over Trump revives a longstanding question: Are major historical outcomes the product of presidential choices or are they largely the result of economic and political forces beyond anyone’s control? Sometimes history seems like a rushing river whose course is shaped by rainfall and topography, but presidents are not simply ants clinging to a log swept along by the current. They are more like white-water rafters trying to steer and fend off rocks, occasionally overturning and sometimes succeeding in steering to a desired destination.

For example, Franklin D. Roosevelt was unable to bring the US into World War II until Pearl Harbor, but his moral framing of the threat posed by Hitler, and his preparations to confront that threat proved crucial. After World War II, the American response might have been very different had Henry Wallace instead of Harry Truman (who replaced Wallace as FDR’s running mate for the 1944 election) been president. After the 1952 election, an isolationist Robert Taft or an assertive Douglas MacArthur presidency might have disrupted the relatively smooth consolidation of Truman’s containment strategy, over which Dwight D. Eisenhower presided.

John F. Kennedy was crucial in averting a nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis and then signing the first nuclear arms control agreement. But he and Lyndon B. Johnson mired the country in the unnecessary fiasco of the Vietnam War. At the end of the century, economic forces caused the erosion of the Soviet Union and Mikhail Gorbachev’s actions accelerated the Soviet collapse. But Ronald Reagan’s defense buildup and negotiating skill, and George H.W. Bush’s skill in managing crises, played a significant role in bringing about a surprising peaceful end to the Cold War with Germany in NATO.

In other words, leaders and their skills matter. This means that Trump cannot be easily dismissed. Like other contemporary leaders, he is being swept along by the strong transnational current of a novel corona virus, but has proven a poor steersman because of inconsistent responses delayed by his narcissism. More important than his vain tweets, however, are his weakening of institutions, alliances, and America’s soft power of attraction which polls show had declined in the past three years even before the COVID crisis. Presidents need both hard and soft power skills. Machiavellian and organizational skills are essential, but so is emotional intelligence, which produces the skills of self-awareness and self-control, and contextual intelligence, neither of which are Trump’s strong suit. Our 46th president, whenever he or she arrives, will confront a changed world, partly because of COVID, but also because of the effects of Trump’s personality and policies. How great that change will be depends on whether he is a one or two term president.