Richard Haass on the Need for Historically Informed Policy in a Changing World

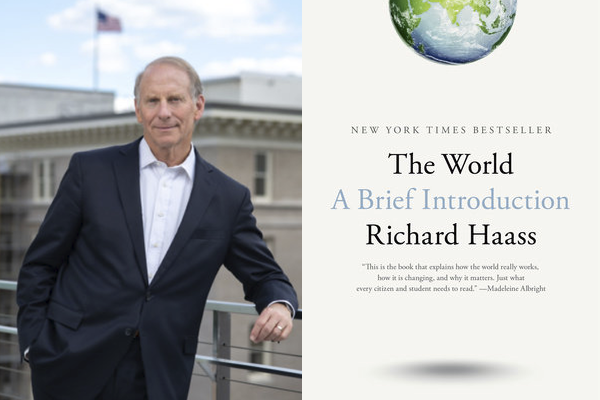

Richard Haass is the President of the Council on Foreign Relations. He served as senior Middle East advisor to President George H.W. Bush and as Director of the Policy Planning Staff under Secretary of State Colin Powell and is the author of fifteen books, most recently The World: A Brief Introduction. He discussed the work and the importance of historical understanding with HNN Contributing Editor David O'Connor.

David O'Connor: Can you share the story of how a fishing trip sparked your interest in writing this book on history and international relations?

Richard Haass: The idea for writing The World: A Brief Introduction was sparked on a summer's day fishing with a friend and his nephew in Nantucket. The young man was about to enter his senior year at Stanford and would graduate with a degree in computer science. As we began talking, it became clear that he had been exposed to little history or politics or economics and would leave the campus with almost no understanding of why the world mattered and how it worked. When I got back to my office, I began looking into this issue and realized that a young American could graduate from nearly any high school or college in the country without taking as much as an introductory course on U.S. history, international relations, international economics, or globalization. To be sure, there are distribution requirements at nearly every college or university, but a student can choose to narrowly focus on one period of history or one region of the world without ever taking a survey course that provides a framework for putting it all together. I decided to write The World to provide that foundation for students or even people who had graduated from college decades ago but need a refresher. A democracy requires that its citizens be informed, and it was evident far too many citizens in the United States and other countries could not be described as globally literate.

Are you an advocate for universities and colleges to mandate a core curriculum? If so, what courses would you want to see included in it?

I am a firm believer in a core curriculum. Students (and their parents) should know before choosing to attend a particular institution just what it is they will be sure to learn. Would-be employers should know what a degree from a particular institution stands for. I believe a core curriculum should at a minimum include courses devoted to promoting critical skills (analysis, writing, speaking, teamwork, digital) and knowledge (world history, civics, global literacy). Such a core would still allow every student to have ample opportunity to specialize.

How have you and your colleagues at the Council on Foreign Relations encouraged those who are not in college to learn about world history and current international events? Which efforts do you think have been the most successful?

We continue to publish Foreign Affairs, which releases a print edition six times per year and remains the magazine of record in the field. The magazine contains articles that present fresh takes and new arguments on international issues - the magazine published the famous "X" article by George Kennan that introduced Americans to the concept of containment, for example. Its website, ForeignAffairs.com, publishes shorter pieces every day more closely tied to the news cycle. On CFR.org we publish a host of backgrounders that aim to provide what a person needs to know to get up to speed on issues ranging from global efforts to find a vaccine for COVID-19 and U.S. policy toward the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to the role of the IMF and the U.S. opioid epidemic. We have also produced a series of award-winning InfoGuides on China's maritime disputes, modern slavery, and refugees, among others. We have a series of podcasts, including The President's Inbox, which each week focuses on a foreign policy challenge facing the United States, and another titled Why It Matters, which takes issues and as its title suggests explains to listeners why they should care about them.

Just as important, a few years ago I created an entirely new education department at the Council. Its mission is explicitly to teach Americans how the world works. Its flagship initiative, World101, explains globalization, including climate change, migration, cyberspace, proliferation, terrorism, global health, trade, and monetary policy, regions of the world, the ideas basic to understanding how the world operates, and, as of early 2021, history. Each topic includes videos, infographics, interactives, timelines, and written materials. It also includes teaching resources for teachers who want to use the lessons in their classrooms. We have also created Model Diplomacy, which helps students learn about foreign policy and how it is made by providing free National Security Council and UN Security Council simulations.

You begin this book with an explanation of the Treaty of Westphalia, one that many people don’t know very well. Why did you start your study in 1648? How have the concepts and practices established in the Westphalian system endured?

I started with the Treaty of Westphalia because the principles enshrined in those arrangements created the modern international system. The treaty (in actuality a series of treaties) established the principle of sovereignty that increased respect for borders along with the notion that rival powers ought not to interfere in the internal affairs of others. These agreements helped bring about a period of relative stability, ending the bloody Thirty Years War that was waged over questions of which religion could be practiced within a territory's borders. More important for our purposes, they put forward the principle of sovereignty that remains largely unchanged to this day. When you hear the Chinese government declare that foreign powers have no right to criticize what happens inside of China's borders, they are harkening back to Westphalia. At the same time, as I argued in my book A World in Disarray, this conception of sovereignty is inadequate for dealing with global challenges. For issues like climate change, global health, terrorism, and migration, what happens inside a country's borders has huge ramifications for other countries. For instance, Brazil's decision to open up the Amazon for commercial purposes and deplete this natual resource has negative implications for the world's ability to combat climate change. China's failure to control the outbreak of COVID-19 has caused massive suffering around the world. I introduced the concept of sovereign obligation to capture the idea that governments have certain responsibilities to their citizens and the world, and if they do not meet those obligations the world should act. The challenge will be how to preserve the basic Westphalian respect for borders (something violated in 1990 by Iraq in Kuwait and by Russia in Ukraine more recently) and at the same time introduce the notion that with rights come obligations that must also be respected.

How did Wilsonian idealism at the Versailles Conference propose to reform the Westphalian model? Why did the effort fail to prevent another world war a couple decades later?

Wilson famously declared the United States had entered World War I because "the world must be made safe for democracy." This was a decidedly anti-Westphalian statement, as he was in essence calling for the United States to transform other societies and influence their internal trajectory. The Treaty of Westphalia, as I mentioned above, emphasized that a country's internal nature was its own business, and countries should instead focus on shaping each other's foreign policies. It is too much to say that Wilson's approach failed to prevent another world war. World War II was the result of a convergence of forces, including the Great Depression, protectionism, German and Japanese nationalism, U.S. isolationism, and the weakness of international institutions, above all the League of Nations. What I would highlight about Wilsonianism is that it remains an important strain of American political thought. To this day, there is a school of American foreign policy that emphasizes the promotion of democracy, and, in some cases, the transformation of other societies. My personal preference is to focus our efforts mostly on shaping the foreign policies of other countries.

I found your coverage of what you call China’s “century of humiliation” to be one of the most interesting parts of the book. What were some of the key developments that led to this troubled period in China’s history? How do you think this “humiliation” affects Chinese domestic and international policies today?

As I mention in the book, the "century of humiliation," as the Chinese term it, began with the Opium Wars and closed with the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949. It was mostly the result of the internal decay of the Qing Dynasty, which was in large part brought on by its inability to grasp the changes that were going on around it and adjust to the new reality. While Japan, following Commodore Perry's mission, modernized and attempted to catch up with the West in areas where it had fallen behind, the Qing Dynasty remained set in its ways, convinced that the world had nothing to offer China. More important, this "humiliation" shapes the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) narrative and how it wants Chinese citizens to think about the world. In the CCP's telling, only a strong government can prevent foreign powers from taking advantage of China, while a fractious and weak country invites foreign aggression. Of course, what the CCP then claims is that only it can provide the stability and strength that China needs and uses this take on history to justify one-party rule and the repression of civil liberties.

Though you do not deny the hardships and missteps that occurred during the Cold War, you do offer a rather positive evaluation of the stability in the decades-long bipolar contest between the US and Soviet Union. What were some of the features of the Cold War that helped manage the tensions between the superpowers and prevent the outbreak of a hot war? Can some of these be applied to the current Sino-American relations?

We should not discount the role that nuclear weapons played in keeping the Cold War cold. Simply put, the specter of nuclear war kept the competition between the United States and the Soviet Union bounded, as any potential war between the two powers could have led to a nuclear exchange that would have decimated both countries and the world. Many international relations scholars argue that a bipolar world is inherently more stable than a multipolar one, because it is easier to maintain a balance of power and stability more broadly when there are only two centers of decision-making. I would add that the United States focused most (although not exclusively) on the Soviet Union's international behavior and did not seek to overthrow the regime. There was a measure of restraint on both sides. Finally, there were frequent high-level summits, arms control agreements, and regular diplomatic interactions. These all helped set understandings for each side and communicate what would not be acceptable to each side.

In terms of Sino-U.S. relations, I believe nuclear deterrence will work to lower the prospect of war between the two countries. I am concerned, though, that we do not have a real strategic dialogue with China. We need to be able to sit in a room with each other and at an authoritative level communicate what we will not tolerate in areas like the South China Sea, the East China Sea, and the Taiwan Strait. The chances of miscalculation are too high. I also believe we should focus less on China's internal trajectory and more on shaping its foreign policy. We cannot determine China's future, which will be for the Chinese people to decide. We should continue to call out the government's human rights abuses in Xinjiang and its dismantling of Hong Kong's freedoms, but we should not make this the principal focus of our relationship. Instead, we should compete with China, push back against its policies that harm U.S. interests, and seek cooperation where possible with China to address global challenges.

In the Cold War era, both Europe and parts of Asia experienced tremendous economic growth, peace, and prosperity. What role did the United States play in facilitating these positive outcomes? Are there lessons from Europe and East Asia that can be applied to other parts of the world today?

First of all, we should give credit to the people of Europe and Asia for their tremendous economic success. In terms of the U.S. role, there was of course the Marshall Plan in Europe that provided the funding Europe needed to get back on its feet and rebuild after World War II. In Asia, the United States gave significant aid to its allies. The point I would make is that this aid was not done purely out of altruism. Instead, it furthered U.S. interests. It ensured Western Europe did not go over to the Soviet Union and that U.S. allies in Asia could be stronger. Foreign aid continues to be an important tool in our foreign policy toolbox, and we should continue to use it to further our interests. For instance, with China extending its reach around the globe through the Belt and Road Initiative, the United States should respond with a better alternative that would provide funding for infrastructure in the developing world but make it conditional on the infrastructure being green and on the countries undertaking necessary reforms. Trade can also be a powerful tool for promoting development.

What are some of the key developments that undermined the great hope that followed the end of the Cold War?

In many ways, the Cold War was a simpler time for U.S. foreign policy. The country had one adversary, and it could devote most of its resources and the bulk of its foreign policy apparatus to addressing it. After the Soviet Union collapsed, containment lost its relevance, and U.S. foreign policy lost its compass. The United States enjoyed unparalleled power, but no consensus emerged as to how it should use that power: should it spread democracy and free market economics, prevent other great powers from emerging, alleviate humanitarian concerns, tackle global challenges, or something else? I've begun calling the post-Cold War period of U.S. foreign policy "the great squandering" given that U.S. primacy was not converted into lasting arrangements consistent with U.S. interests.

I would point to a few U.S. missteps that set back its foreign policy agenda and undermined the hope you refer to. First there was the mistaken 2003 invasion of Iraq, where the United States initiated a war of choice in the hope of transforming the country and the region. The Iraq War, and the nation-building effort in Afghanistan, soured many Americans on their country playing an active role internationally. Simply put, they believed the costs of such a role outweighed the benefits. Now, as the United States faces challenges from China to Russia, Iran, and North Korea, Americans are weary of getting involved. Relations with Russia soured, some would argue at least in part because of NATO enlargement. The 2008 global financial crisis raised doubts worldwide about U.S. competence, as has the American response to COVID-19. In short, the relative position and standing of the United States have deteriorated.

After World War II, the United States helped construct what you call the liberal world order. What are the key features of this order? What do you consider its greatest strengths and weaknesses?

The liberal world order is an umbrella term for the set of institutions the United States helped to create in the wake of the Second World War, including the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (now the World Trade Organization). It was rooted in liberal ideas of free trade, democracy, and the peaceful settlement of disputes, and was also liberal in the sense that any country could join the order as long as it abided by its principles. It was never truly a global order during the Cold War, as the Soviet Union and its satellite countries opted out of many of its elements.

The great strengths of the liberal world order are that it has promoted unprecedented peace, prosperity, and freedom. But increasingly it is being challenged. Its liberalness is rejected by authoritarian regimes. Many governments or non-state actors are not prepared to hold off using force to advance their international aims. In addition, the order has had difficulty adjusting to shifting power balances (above all China’s rise) and in developing collective responses to global challenges such as climate change, proliferation, and the emergence of cyberspace.

China’s emergence as a world economic power has greatly challenged this liberal world order and efforts to get it to conform to some of its basic principles have come up short. How can other countries persuade and/or pressure China to adhere to the practices and rules of institutions (e.g., the World Trade Organization) dedicated to upholding the order?

First, it is fair to say that some institutions, such as the WTO, were not set up to address a country such as China, with a hybrid economy that mixes free market enterprise with a large state role. And the WTO failed to adjust sufficiently to China’s rise. The United States should be working with its allies and principal trading partners to bring about a major reform of the WTO. More broadly, the single greatest asset that the United States enjoys is its network of alliances. China does not have allies, whereas the United States enjoys alliances with many of the most prosperous and powerful countries in Europe and Asia. The United States needs to leverage those alliances to present a united front in pushing back where China does not live up to its obligations. It should also work with its allies to develop an alternative 5G network, for example, and negotiate new trade deals that set high standards and would compel China to join or risk being left behind. In the security realm, it should coordinate with its allies in Asia to resist Chinese claims to the South China Sea and make clear to China that any use of force against Taiwan would be met with a response.

Despite the fact that the US was a driving force behind establishing and maintaining this liberal world order, many Americans have grown weary of the costs involved and fail to see how it benefits them. Indeed, this was a key feature in President Trump’s 2016 campaign message and continues to influence his foreign policy. How can policymakers who want to continue American leadership in this order persuade Americans that the system actually benefits them?

Policymakers need to be more explicit in highlighting the benefits of the liberal order and contextualizing its costs. We avoided great power war with the Soviet Union and the Cold War ended on terms more favorable to the United States than even the most optimistic person could have imagined. Global trade has skyrocketed, and America remains the richest country on earth. Alliances have helped keep the peace in Europe and Asia for decades. In terms of the costs, defense spending as a percentage of GDP is currently well below the Cold War average, which was still a time Americans did not have to make a tradeoff between butter and guns. We can assume a leadership role abroad without sacrificing our prosperity. On the contrary, playing an active role internationally is necessary in order to keep America safe and its people prosperous. The United States may be bordered by two oceans, but these oceans are not moats. Even if we choose to ignore the world, it will not ignore us. Both 9/11 and the COVID-19 pandemic have made this abundantly clear.