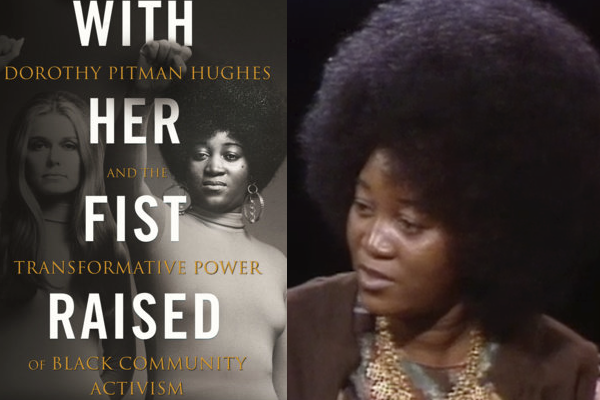

With Her Fist Raised: Dorothy Pitman Hughes and the Transformative Power of Community Activism

Dorothy Pitman Hughes, 1973. From WNED TV series "Woman"

In 1969, a young reporter for New York magazine visited the West 80th Street Day Care and Community Center directed by Dorothy Pitman Hughes. Begun as an at-home child care for neighborhood children, Dorothy’s center grew from rooms in a welfare hotel to a former Chinese restaurant on West 80th Street. Despite its humble origins and surroundings, the reporter recognized that the day care center was a locus of power, a “neighborhood-changing, life changing” place. Described by the reporter as possessing a "natural gift for organizing," Dorothy used the Center to create community-controlled resources that provided job training, a Youth Action Corps, housing assistance, protection from domestic violence, and food resources on the Westside of Manhattan before gentrification. That young reporter, who was justifiably impressed with Dorothy in 1969, was Gloria Steinem.

At that same time, Dorothy and Gloria were becoming more involved in the emerging women’s movement and they began to spend more time together, collaborating and organizing. Gloria often credits black feminists for teaching her about feminism and Dorothy is at the top of that list. She also credits Dorothy with helping her deal with her fear of public speaking. As a singer and activist comfortable in front of a crowd and willing to lead occupation protests of city offices, Dorothy persuaded Gloria to speak publicly and gave her advice about how to do it effectively. Together they took to the podium, speaking against inequality and injustice, while addressing the women’s movement, childcare, and welfare. At the time, Dorothy was the better-known activist, and certainly more involved in a wider range of political causes. Yet Dorothy has not been included in histories of the women’s movement, the civil rights movement, or even New York City community politics.

Dorothy Pitman Hughes’ adult life has been one of continual activism. When she moved to New York from rural Georgia in the late 1950s, she remembers becoming involved in everything that she could that “represented Civil Rights, Human Rights and Equality.” From her first efforts raising funds for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in the early 1960s, Dorothy turned her attention to the conditions in her West Side neighborhood. Because she worked nights as a nightclub singer, Dorothy witnessed children in her neighborhood while she was at home during the day “doing the cooking, cleaning, and clothes washing,” and even “taking care of babies,” as their parents worked. As Dorothy started a community day care for these children, she had the revelation that this was not simply a childcare issue. Dorothy realized that entangled with the children of the West Side were issues of racial discrimination, poverty, drug use, sub-standard housing, welfare hotels, lack of job training, and even the Vietnam War. This is why the childcare center that Dorothy imagined and created was essential: It became a center for the community to define its needs, fashion its own solutions, and take to the streets in protest when it was called for.

As a community activist, Hughes was deeply involved in a series of political organizing efforts that began with CORE in the 1960s, extended to community organizing in New York City, fundraising and campaigning for the Democratic Party, and lobbying to include women in the decision processes behind the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone. Over the course of her career, Dorothy was a founder of the West Side Community Alliance, the Women’s Action Alliance, and the Agency for Child Development in New York City. She was active in the Harlem Business Alliance, the National Black Women’s Political Congress, the National Welfare Rights Organization, the National Council of Negro Women, and Women Initiating Self-Empowerment. The influential, non-sexist TV special, Free to Be … You and Me was filmed at the West 80th Street Child Care Center.

By the 1980s, Dorothy had left the West Side for Harlem and was transitioning away from work as a Center organizer to that of a business owner and entrepreneur. Along the way, she bought the franchise for the Miss Greater New York City Pageant. Like many feminists, the pageant process disturbed Dorothy, but not because it objectified women. She saw the pageant as overwhelmingly white and wanted to showcase the beauty of African American women. Dorothy's stint as a pageant owner was short-lived but prescient, as Vanessa Williams would win the Miss America title within two years of Dorothy’s efforts.

Beauty pageants gave way to Dorothy’s store, Harlem Office Supply, a community center of a different sort -- this time organizing around economic empowerment, especially for women in Harlem. Used to dealing with government programs, Dorothy saw President Clinton’s 1994 creation of the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone as a tremendous opportunity for herself and other African American business people in Harlem. She organized Harlem women to own and run their businesses with the hope of government support, only to be disappointed when those opportunities went to national chains, not local owners. For Dorothy, the gentrification of Harlem became a form of “ethnic cleansing” as African American business owners were moved out under the guise of “economic empowerment.” Her own Harlem Office Supply was replaced by a Staples.

Finding Hughes’ place in these histories produces a history of the women’s movement with children, race, and welfare rights at its core, a history of women’s politics grounded in community organizing and African American economic development.