Liberty, Freedom, and Whiteness: Reviewing Tyler Stovall's "White Freedom"

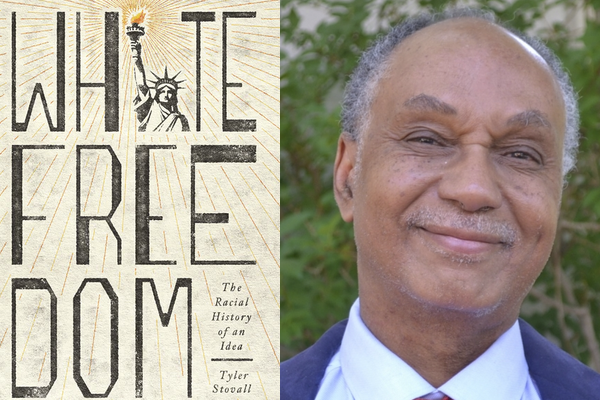

White Freedom: The Racial History of an Idea by Tyler Stovall (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University press, 2021)

Tyler Stovall, a professor of history and the Dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Fordham University, is a European historian specializing in the history of France. In 2017, Stovall was President of the American Historical Association. In White Freedom: The Racial History of an Idea, Stovall defines “white freedom as the belief (and practice) that freedom is central to white identity, and that only white people can or should be free” (11). While the definition of white freedom does not necessitate it, Stovall believes that in practice white freedom meant the subjugation of other races, both to preserve and justify a system that privileged people of European ancestry. It is a history “replete with paradoxes” (18). The era of the European Enlightenment was also the apex of the trans-Atlantic slave trade (102).

Starting with the seventeenth century European Enlightenment, Stovall traces the way liberty (individual rights) and freedom (the absence of restraint) for whites was based on the exploitation of people of African ancestry in colonized territories and in metropolitan centers. Stovall, focusing on France and the United States, argues that “two seemingly opposite philosophies, liberty and racism, are in significant ways not opposites at all” (x). They are reinforcing concepts of the same social system. He cites Edmund Morgan’s study of colonial Virginia where Morgan argues “Racism made it possible for white Virginians to develop a devotion to the equality that English republicans had declared the soul of liberty” (13). Whites in Virginia learned to prize their shared freedom so highly because “they could see every day what it meant to live without it” (12).

Stovall’s book is especially timely given debate in the United States between supporters of the 1619 Project and 1776 Unites over the lingering impact of slavery and racism on contemporary American society. He opens the book by pinpointing what may be the ultimate irony in the history of the United States, that the American “Temple of Liberty,” the Capitol, was constructed, at least in part, by enslaved Africans. In a second irony, when Congress acknowledged this history in 2007, it renamed the building’s Great Hall as Emancipation Hall to recognize the work of the enslaved Africans. Stovall questions the choice of the new name because it was unlikely any of the Africans lived long enough to be emancipated. He calls the name a “mockery” that ignores their actual history and the way liberty has always been identified with and reserved for “whiteness” (5). Liberty and race, to Stovall, are at the core of “white identity” in the past and in the United States today, as racism has shaped the identity of those denied “whiteness.” People of color have historically had to struggle to overcome the identification of freedom with whiteness and to redefine it to include all humanity (7).

White Freedom is divided into three sections with two extended chapters in each section. Part 1 is both more philosophical and more narrowly focused than chronologically historical, with chapters on alternative idea of freedom and the Statue of Liberty as a symbol of freedom. Part 2 examines the relationship between race and freedom in the Enlightenment period and the 19th century while Part 3 extends discussion into the 20th century up to the tearing down of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the collapse of Soviet communism. Stovall concludes with a brief discussion of the post-Cold War world, but stops short of examining more recent rightwing “populist,” ethno-nationalist, and neo-fascist movements in the United States and other areas of the world. He does associate the post-9/11 war on terrorism (Islam) and President Trump’s effort to build a wall to separate the United States from Mexico with past racist ideology and practice. Unfortunately readers of this book do not get to learn his views on the significance of the elections of Barack Obama and Kamala Harris or of the Black Lives Matter Movement, although he has commented on them in other places.

In Chapter 3, Stovall’s recounting of the revolutionary generation’s condemnation of British tyranny, coupled with their own endorsement of African slavery, what he labels a “bizarre spectacle,” is especially well done. There is widespread panic, especially in the southern colonies, that the British will employ formerly enslaved Africans to crush the rebellion, both before and after the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, issued a proclamation in November 1775 promising freedom to enslaved Africans who fought for the British (118). Colonial leaders, at least some of them, understood their hypocrisy. In my classes I reference a 1773 letter by Patrick Henry to Robert Pleasant, something not mentioned by Stovall, where Henry wrote that he abhorred the “lamentable Evil” and could not justify it, however was committed to its continuance:

Would any one believe that I am Master of Slaves of my own purchase! I am drawn along by ye. general inconvenience of living without them, I will not, I cannot justify it. However culpable my Conduct, I will so far pay my devoir to Virtue, as to own the excellence & rectitude of her Precepts, & to lament my want of conforming to them.

Because he is grounded in both American and French history, Stovall is able to give important recognition to the Haitian slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue, an actual struggle for freedom, that strikes fear in European colonial empires and American enslavers by challenging their limited white only version of freedom. Stovall mentions Alexis de Tocqueville on multiple occasions, but I was surprised he did not quote the passage from de Tocqueville’s1835 Democracy in America where he commented on the “Situation of the Black Population in the United States, And Dangers with Which its Presence Threatens the Whites.” In a passage that supports Stovall’s thesis, de Tocqueville, with incredible prescience, wrote:

I do not believe that the white and black races will ever live in any country upon an equal footing . . . A despot who should subject the Americans and their former slaves to the same yoke might perhaps succeed in commingling their races; but as long as the American democracy remains at the head of affairs, no one will undertake so difficult a task; and it may be foreseen that the freer the white population of the United States becomes, the more isolated will it remain.

The United States today is a product of the failed effort at Reconstruction following the American Civil War. This was very much, as Stovall points out, the result of Northern ambivalence toward ending slavery and rejection of racial equality. In the end, for most white Northerners, freedom for the formerly enslaved just meant the end of slavery. With the Compromise of 1877, the federal government surrendered the future of freed men and women to former slaveholders who resumed control over Southern institutions. This was facilitated, in part, by the assimilation of new waves of European immigrants into whiteness, providing a low wage workforce for an expanding industrial giant, and an expanded white political majority that cemented de Tocqueville’s perception of a racially divided America in place.

Stovall has a very interesting take on the impact of World War I and II on America’s racial ideology. He sees both wars further racializing American society as the United States battled stereotyped German and Japanese racial enemies and used racist propaganda to mobilize the home front. After World War II, the United States emerged as an imperial power at war with East and Southeast Asians who again were racially stereotyped. Stovall has one chapter sub-head that aptly captures his view of these developments, especially the Treaty of Versailles rejection of nationalist aspirations in the non-white colonized world, “Making a World Safe for Whiteness” (204).

Stovall documents how white America responded to a Black sense of possibility after World War I with racial violence intended to suppress any possibility of change. At the same time, pseudo-scientific intellectuals championed a racial hierarchy that led to the exclusion from whiteness, at least temporarily, of Southern and Eastern European immigrants, largely Jews and Southern Italians. During the post-war period there was a rise in Klan activity in the United States and Nazi ideology in Europe that expressly mirrored United States treatment of African and Native Americans (219). World War II was portrayed as a war to promote freedom, but as Gandhi pointed out, it was a “hollow” declaration “so long as India, and for that matter Africa, are exploited by Great Britain, and America has the Negro problem in her own home” (228).

While there were important shifts in racial policy in the United States during World War II, Stovall believes that the overall picture was the persistence of discrimination, segregation, and violence aimed at Blacks who sought to improve their situation and argued for “Double V,” victory over fascism in Europe and racism at home. However, “the most egregious example of racial discrimination in America during World War II was the internment of Japanese Americans” (238). Stovall argues that the internment of Japanese Americans, rather than being an exception, represents an “extreme example of the over-arching theme of white freedom” in American history (239).

Stovall sub-titles his discussion of the post-World War II world “The Fall and Rise of White Freedom During the Cold War” (247). The weakening of British and French empires and their mobilization of colonized people to support the war effort, contributed to a post-war surge in independence movements and unprecedented challenges to white freedom across the globe and in the United States by the African American Civil Rights Movement. Stovall has an interesting take on the Cold War, one I accept but don’t entirely agree with. Instead of positing it as a conflict between capitalism and communism or democracy versus totalitarianism, as it is in standard narratives, Stovall argues “Western cold warriors were outraged by the denial of freedom and independence to the white nations of Eastern Europe, an outrage that certainly did not extend to the absence of self-determination for the [non-white] peoples of the colonial world” (252). The European colonial powers and the United States fought a series of anti-independence wars in Africa and Asia and the United States repeatedly intervened in Latin America and the Caribbean to suppress liberation movements.

Stovall argues that the history of the Civil Rights movement in the United States has to be understood as intricately interwoven with the history of the Cold War, as with the decolonization movements abroad; it argued for the extension of fundamental rights, freedom, to all people. “Freedom was the ultimate goal of the worldwide struggle against racism” (270). Yet despite gains in voting rights, educational opportunity, and access to public facilities, and new taboos on overtly racist language, the Civil Rights Movement was met, not by white acceptance, but by white resistance and a “new variant,” of white freedom. Globally, newly independent nations remained dependent on and dominated by the former colonial powers and their international agencies and ripped apart by wars rooted in ethnic conflicts exacerbated by colonial regimes. In the United States, a white backlash against school and housing desegregation efforts elected right leaning governments. Legal limits were placed on affirmative action programs and school integration efforts. Social service budgets were cut at the same time that police funding to protect white communities was increased.

One of the things that make the book most engaging and thought provoking is Stovall’s ability to muse about a wide range of material including literary, artistic, and cultural references. Chapter 1 begins with a long discourse on Peter Pan (1904) by J.M. Barrie. Stovall argues that the lesson of the original play, not the Broadway or Hollywood versions, is that “savage freedom inexorably gives way to white freedom,” which Barrie equates with middle-class Edwardian society, not the fantasy Neverland, which, after all, is a never land inhabited by racialized (“redskins”) and criminalized (pirates) others (24). Later Stovall compares Napster, the now illegal computer program that permitted user the “freedom” to share downloaded music files, with romanticized notions of pirates such as the one depicted in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883); they were the ultimate free men unbounded by the constraints of civilization (39). Chapter 3 starts with a discussion of Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute (1791) as a representation of the triumph of light over darkness, the victory of “brotherhood, enlightenment, and liberty” (99). However, Stovall argues there is also a racial dimension to the opera that portrays the dual victory of white Enlightenment Europe over monarchy and the savagery of a Moorish slave who attempted to rape the heroine and then allied with the Queen of Night (99-100). Chapter 4 begins with the debate over whether Heathcliff, the protagonist in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847), who is described with dark metaphors and as having a semi-savage nature, had at least partial African ancestry (134).

The battle over the meaning of the Statue of Liberty is one of the essential American paradoxes that Stovall highlights. The statue presents Liberty as a white lady on a pedestal that welcomes white, European, immigrants to New York harbor. But she is also the “white Goddess” in the poem “Unguarded Gates” (1895) by the nativist Thomas Bailey. Bailey chides the statue for failing to protect America from the “wild motley throng” whose “tiger passions” threaten to destroy white, Anglo-Saxon America (85-86). In class, I have students compare the images presented in Bailey’s poem with Emma Lazarus’ “New Colossus” (1883). They discover that the nativist version wins out as the United States passes increasingly restrictive immigration laws culminating in 1924 with a virtual halt to immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe. Stovall notes that it was not until after World War II that Lazarus’ vision, and European immigration, became more broadly acceptable in the United States (90). He believes that even with this broader vision, the Statue of Liberty remains the “world’s greatest representation of white freedom” (95).

Stovall demonstrates the breadth of his scholarship in his discussions of childhood as an example of immature freedom and of adolescence as a period of greater maturity with rebellion against restraint and a greater acceptance of norms. He is also fluent with pseudo-scientific studies where Europeans and white Americans tried to establish a scientific basis for defining race and justifying racial inequality and racism (108-111).

One point of disagreement I have with Stovall is his tendency to use liberty and freedom interchangeably. French and American Enlightenment documents, including the Declaration of Independence (1776) and the Declaration of the Rights of Man (1789), defend liberty or individual rights from oppressive government. The United States celebrates the Sons of Liberty, the Bill of Rights, and the Statue of Liberty. France has the revolutionary slogan “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité,” as well as “Liberty leading the people” (1830), the famous painting by Eugène Delacroix where Miss Liberty leads the people, white people, against tyranny. Free for Jean-Jacques Rousseau (“Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains”) and especially freedom to America’s founders, simply meant the opposite of enslavement. It is not until Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (1863) and his call for a “new birth of freedom,” that the idea of freedom is irrevocably connected with democratic government (Foner, 1998). Stovall acknowledges that when “Enlightenment writers talked about the evils of slavery they did so only in a metaphorical rather than literal sense” and they were primarily concerned with their felt oppression by the church and monarchical state (107). Leading European Enlightenment figures like John Locke, David Hume, and Voltaire profited from slavery and the slave trade (108). For them, their liberty was very different from the freedom of others.

Reading White Freedom gave me the chance to reconnect with someone I knew fifty years earlier when we were counselors at Camp Hurley, an interracial program in the Catskill Mountains of New York State that attempted to build bridges across America’s racial divide. I am white and Tyler is African American, something I was surprised he did not mention in the book, although it is clear from his cover photograph. In the preface he talks about his father, a World War II veteran who was stationed in Europe, but not about what the experience meant to an African American solider in a segregated military. Stovall acknowledges the personal nature of the subject of this book and I wish he had personalized it more with his own experience as a Black man and the father of a Black son.

Whether you agree with Tyler Stovall’s over all theme or specific points, there is no question that this this is an excellent work of comparative and integrative history that deserves a wide academic and general audience. Stovall believes the history of white freedom as documented is his book is “both a sobering tale and one full of hope, and if the past is a guide I consider myself justified in believing that hope will prevail in the future” (321). I also hope so.