Ambitious for War: How German-Soviet Collaboration Set the Course for WWII

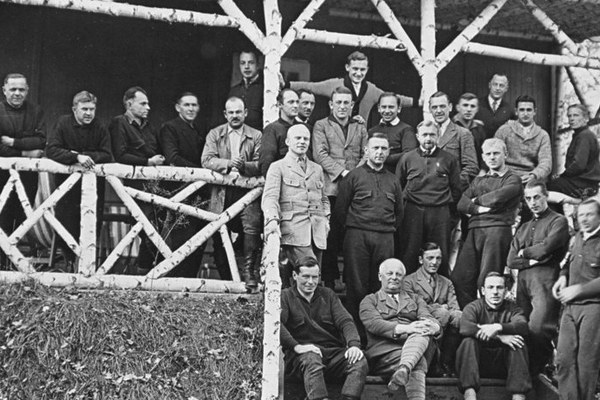

German staff at the Tomka chemical weapons facility in the USSR, 1928

In the early morning hours of June 22, 1941, the Soviet-German frontier exploded with the sounds of combat. It began with German artillery and airstrikes pounding Soviet border positions and annihilating nearly fifteen hundred Soviet aircraft in a matter of hours. Bombers struck Soviet bases as far away as Sevastopol and Kiev. Three million German soldiers soon crossed the border, marking the beginning of the largest invasion in human history.

Never before in history had two adversaries spent so much time arming each other for war. German soldiers marched into the Soviet Union on rubber boots made from material imported from the USSR. The ammunition they carried contained chrome, manganese, nickel and steel mined in the Soviet Union. Their vehicles ran on Soviet-produced gasoline. German tanks and aircraft drew from engineering and testing work conducted in the USSR; most German tanks included key component parts borrowed from Soviet designs. Those in command were intimately familiar with the Red Army, as many of the leading German generals had lived, studied, and worked in the USSR, including Generals Heinz Guderian, Erich von Manstein, Wilhelm Keitel, Walter Model and around forty other officers of general rank.

Across the lines, the story was much the same. The Soviet High Command – Stavka – was modelled on its German counterpart. Three of the Soviet Union’s five marshals in 1941 had studied alongside their future opponents, including the Chairman of Stavka Semyon Timoshenko. German officers embedded in Soviet military academies had helped to train thousands of other Soviet officers, too. The equipment that the Red Army would use to fight the Germans borrowed heavily from German designs, and in some instances were actual copies of German equipment produced under license agreements with German firms before the war began. Many Soviet tanks, aircraft, and warships used German-designed engines. Those weapon systems were often built in factories that had been financed by German firms, constructed or equipped by German engineers, and powered by coal that had been imported from Germany.

Twenty years of intermittent cooperation had thus armed both Germany and the USSR for war. That relationship had begun in the immediate aftermath of the First World War. In the Treaty of Versailles that ended the war, the victorious allies reduced the German Army to only 100,000 men, and banned it from purchasing or producing tanks, aircraft, submarines or chemical weapons. They also stationed inspection teams in Germany to supervise the demilitarization of German industry. The remnants of the German High Command, now leading the much reduced Reichswehr [Reich Defense Force], did not accept these limitations. Instead, they immediately sought ways to circumvent Versailles and its enforcers. But isolated and occupied, they needed a partner.

The Reichswehr would find one a thousand miles to the east. After their victory in the Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks found themselves largely cut off from the rest of the world. The Red Army was in parlous shape. Famine and disease were rife. And industrial production had dropped to nearly zero. Facing the hostility of much of the rest of the world, Soviet Russia needed help, even if it meant working with the arch-counter revolutionaries heading the German Army.

Circumstances thus thrust together ideological opponents. The German military began to provide the Soviets materiel and intelligence during the Bolsheviks’ war against Poland in 1920. In April 1922, the two states normalized relations in the Treaty of Rapallo. Shortly thereafter, the two militaries expanded cooperation, beginning with the relocation to the USSR of industrial production banned in Germany. The first products of this effort would be a chemical weapons complex near Samara and an aircraft factory in the Moscow suburbs; each began production in 1923.

The scale of industrial cooperation between the two states would grow to staggering proportions, much of it mediated by the German military. In the 1920s alone, the Red Army negotiated contracts with 255 German companies, including nearly every major industrial firm in Germany. The long-term impact on Soviet industrialization was tremendous: By 1940, 55% of all Soviet tank production would be dependent on factories that had been built or designed by German engineers, or equipped with German machine tools.

As these corporate projects took off, German and Soviet military leadership also sought to expand direct military-to-military cooperation. In 1923, the Reichswehr began to dispatch German pilots to a Soviet air base near Lipetsk. There they trained Soviet cadets on basic flight techniques. In 1925, the Germans would acquire the base on a lease, providing a space where the Reichswehr could test new plane prototypes and train new pilots, mechanics and engineers; in exchange, they would train in Soviet officers and engineers and provide the Soviet Air Force access to Germany’s newest technologies.

Lipetsk was the first of a network of shared military facilities. The next, a chemical weapons testing ground, opened in the fall of 1926 near Moscow. Starting in 1927, construction also began on a joint armored warfare training and testing ground. Based near Kazan, this facility would become fully operational with the arrival of German tank prototypes in 1929.

These facilities provided the basis for future German rearmament. All but one of the seven aviation firms in Germany were secretly contracted to dispatch their prototypes to Lipetsk for testing. Almost all of Germany’s aircraft designers who worked in the Second World War had their first major professional experience designing aircraft for Lipetsk. In essence, Germany would have been largely incapable of mass-design and production of combat aircraft without the Soviet partnership. The same was true in tank design: beginning in 1926, major industrial firms – Daimler, Krupp and M.A.N. – dispatched entire teams of engineers to take up residence at Kama, where Germany’s first new (and secret) tank prototypes were tested and improved. The engineers who resided in the USSR would later be responsible for designing the Panzer Mark I, II, III and IV - Germany’s main tank designs through 1943. These vehicles were in turn based on the prototypes that had first been tested and developed in the USSR.

The facilities in the USSR trained relatively small numbers of German officers and men - less than a thousand in total. Twenty-two future Luftwaffe generals of three star rank or above had either studied, taught, or had a command position at Lipetsk. Seventeen of the students who had attended Kama would command at least a division in combat in the Second World War. Other alumni would manage training as the German military grew, as few other German officers had experience with tanks or planes. In sum, the German military would not have been capable of expansion or rearmament had it not been for the work conducted in the USSR.

This first period of Soviet-German cooperation would come to a close under Hitler in the fall of 1933. In early 1939, the Soviets and Germans would both begin reassessing the possibility of revisiting their earlier partnership. The result would be the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 23, 1939 - a “renewal,” in Hitler’s words, of the earlier period of Soviet-German cooperation. The two states proceeded to partition Eastern Europe into spheres of influence. The following month, Hitler invaded Poland, triggering British and French declarations of war. For the next twenty two months, the Soviets and the Germans would again operate as partners. This second period of partnership would end with Hitler’s betrayal in June 1941. Hitler decided on war with the USSR in December 1940, following his failure to convince Stalin to join the war against Great Britain – there were limits to the dictators’ pact. Nevertheless, by then, thanks to years of collaboration, Germany and the Soviet Union shared a border, a capacity for making war, and bloody-minded ideologies, setting the stage for the most violent front of the Second World War.