When World War II Pacifists "Conquered the Future"

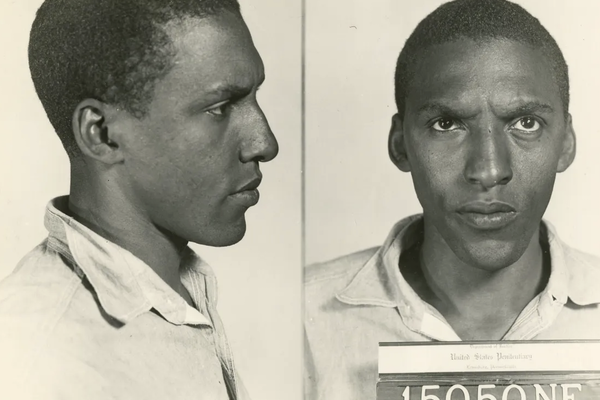

Bayard Rustin's intake mugshot, Lewisburg Penitentiary, 1945. Rustin was incarcerated for resistance to the military draft prior to American entry into the second World War.

War by Other Means: The Pacifists of the Greatest Generation Who Revolutionized Resistance by Daniel Akst (Melville House, 2022)

Nuclear war moved closer to the realm of possibility in 2019, when the Trump administration withdrew the U.S. from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. It became even more conceivable last month, when Russia stopped participating in the New START treaty, which called for Russia and the U.S. to reduce their nuclear arsenals and verify that they were honoring their commitments.

No doubt Max Kampelman would have been alarmed. An American lawyer and diplomat who died in 2013, Kampelman negotiated the first-ever nuclear arms reduction treaties between the two superpowers, in 1987 and 1991. He was also an ex-pacifist who had gone to prison during World War II for refusing to be drafted. There, he volunteered as a guinea pig in a grueling academic study of the effects of starvation.

Kampelman is one of the constellation of pacifists, anarchists, and other war resisters who we meet in Daniel Akst's fascinating new book, War by Other Means: The Pacifists of the Greatest Generation Who Revolutionized Resistance (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2022). The subtitle suggests one of the difficulties of writing such a book. The war against fascism was certainly one of the most justifiable and enduringly popular wars of all time, yet the people Akst is concerned with opposed it.

They were not admirers of Hitler and his allies; rather, they feared that the highly mechanized, technocratic warfare that was developing in the mid-20th century would turn their own country into something nearly as vile as Nazi Germany (“the adoption of Hitlerism in the name of democracy,” as the Socialist presidential candidate Norman Thomas said). And they made their resistance count for something: opposing the bombing of civilian targets in occupied Europe, pleading for the admission of Jewish refugees by the foot-dragging Roosevelt administration, demanding an end to internment of Japanese-Americans, documenting abuses in mental hospitals to which some were assigned, and campaigning against Jim Crow in the federal prisons that many of them found themselves in.

These pacifists were not famous at the time. While Americans knew generally that some conscientious objectors, or COs, were refusing to serve, very few were aware of the far-reaching political ferment that was going on in prisons, in CO camps established in rural parts of the country, and in the pages of pacifist newspapers and pamphlets that circulated during the war. Some would become well-known much later, however, including future civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, war resister David Dellinger, and their mentor, A.J. Muste, executive director of the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOE) and apostle of nonviolence. Better known, marginally, were the Catholic Worker founder Dorothy Day and the radical journalist and political theorist Dwight Macdonald.

Afterward, their influence grew, thanks in part to the tactics and arguments they developed during the war, and in part to the nuclear arms race, which confirmed their warnings about the nature and direction of modern warfare. Many former COs moved directly into the campaigns against nuclear armaments. They helped formulate the strategy of nonviolent resistance that underpinned the Civil Rights Movement and the mass demonstrations and draft resistance that galvanized the campaigns against the Vietnam War. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was founded in 1942 as an offshoot of the FOE and a product of Rustin and Muste’s conviction that ending racial segregation would be the next great struggle after the war ended. The abuse that Rustin and the anarchist poet Robert Duncan withstood owing to their homosexuality draws a through-line from wartime pacifism to the later gay rights movement. The tactics of direct action, civil disobedience, and media-savvy public protest that pacifists developed during World War II would help all of these movements, not to mention environmentalism and AIDS activism, achieve their greatest successes.

Akst’s story begins even before the U.S. entered the war, when the “Union Eight”—Dellinger and seven other students at Union Theological Seminary—refused to register for the draft. They would serve nine months in federal prison at Danbury, Connecticut, and would be in and out of prison and in trouble with the authorities for the remainder of the war. COs staged work stoppages, slowdowns, and out-and-out strikes both in federal prisons and in the rural Civilian Public Service (CPS) camps where many were sent to work on irrigation projects and the like—until they became incorrigible, that is.

Nor was resistance always strictly peaceful. COs were not paid for their work as internees. At one CPS camp in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, COs responded by launching a campaign of vandalism and sabotage that included clogging toilets, hiding lightbulbs and silverware, and scrawling obscenities. On leave in a local town, one group of “conchies” disabled their vehicle, got drunk at local bars, and got into a fight with a soldier. Some pacifist leaders urged COs to cooperate, at least tacitly, once they were in the camps, but in many cases found this impossible. But in federal prisons, especially, pacifists showed solidarity with other prisoners—notably African Americans—and struggled to maintain their activism behind bars.

Akst’s protagonists were complex, difficult individuals who quarreled with each other and with friends and family who wanted to keep them out of trouble. As such, their lives did not follow a strict pattern. But Akst has the gift for weaving together the stories of a group of highly distinctive activists—Dellinger, Rustin, and many less famous names—into a lucid narrative while digging deep into their personalities and beliefs.

He pinpoints some similarities: Many of his protagonists had a conversion experience of one or another sort (Muste had multiple conversions during his long life). Many were Quakers or liberal Protestants with intellectual roots that stretched back to 19th century Abolitionism. Many were inveterate dissidents, never ready to declare victory and settle down. Above all, they were seekers; for Macdonald, Akst writes, the war was “a way station on a lifelong ideological pilgrimage,” and this could apply to nearly everyone Akst re-introduces in his book.

If anything brought them all together, it was an emerging philosophy or worldview that Day called “personalism,” and which Akst characterizes as “a way of navigating between … the corpses of capitalism and communism” at a time when the Depression had discredited the one and Stalin’s tyranny had destroyed any confidence in the other. More deeply, it was a way of reconciling the “sacredness and inviolability of the individual” and the need for collective action against injustice and the death cult of war.

In their own way, each of the activists who emerged from the war—even if they no longer adhered to pacifism—believed that “each of us, driven by love, had the power to change the world simply by changing ourselves.” It was a “mushy and idealistic” notion, Akst observes, but his subjects could be quite hardheaded and sensible when it came to organizing, and it had great moral force in the decades after the war, for Martin Luther King, Jr., among many others.

In purely practical terms, the lessons the World War II resisters carried away from the war represented a break from the top-down organizing of the Old Left that is still playing itself out, Akst notes. They were “wary of authority, often including their own, and longed for direct democracy and communitarian social arrangements,” and “cherished the specific humanity of each and every person.” The result was a preference for non-hierarchical, anarchist-inspired organizing that can be traced in the movement against corporate globalization, the Occupy movement, and the Movement for Black Lives.

These inclinations have created their own problems in the years since the war. The New Left that evolved out of the Civil Rights and antiwar movements never managed to win over the increasingly rigid mainstream of the American labor movement. It had trouble, generally, sinking deeper roots into working and oppressed communities looking for immediate political solutions to their problems. And it largely failed to establish institutions of resistance that could endure without being coopted by the State.

Akst grounds his protagonists’ accomplishments as well as their failings in their individual personalities; when your activism is a part of a lifelong intellectual pilgrimage, staying pinned down to one philosophy or strategy is difficult. Nevertheless, “to a great extent Dellinger and his fellow pacifists did conquer the future,” Akst writes, and on a host of issues—racism, militarism, authoritarianism, and the looming threat of the Bomb—they broke through where others were often afraid to make a fuss. Channeling their principles into a more enduring resistance is the necessary work of their successors.