Hidden Stories of Jewish Resistance in Poland

In 1959, writing about the Holocaust, scholar Mark Bernard highlighted that Jewish resistance was almost always considered a miracle, ethereal, beyond research scope. Still today, this impression generally persists. And yet, Jewish defiance was everywhere during the war, carried out in a multitude of ways, by all types of people.

I first encountered this phenomenon several years ago, when I accidentally came across a collection of Yiddish writing by and about young Polish-Jewish women who rebelled against the Nazis. These “ghetto girls” paid off Gestapo guards, hid revolvers in marmalade jars, and built underground bunkers. They flung homemade explosives and blew up German trains. I was stunned. Why had I – a Jewish writer from a survivor family, not to mention a trained historian who held a Ph.D. in feminist art — never heard this side of the story?

And so began my research. As I discovered, due to preconceived notions of gender, the girls’ educations, and the lack of evident markers of their Jewishness (i.e., circumcision), women played a critical role in the Jewish underground in Poland. But when I set out to write their story and sought a chronological context, it quickly became apparent that there was none. No comprehensive history of the men in the underground existed either. Sure, excellent academic biographies and case studies of rebellions in particular ghettos and camps had been published, but there were no recent English books that relayed the tale of Jewish resistance in the country as a whole. As much as I was baffled by the ferocious female fighters, I was equally baffled by the entire Jewish effort in Poland, the epicenter of the bloodshed, where 3 million Jews (90% of the pre-war population) were savagely murdered. The truth was, though I’d heard of the Warsaw ghetto uprising, I had no idea what actually happened. I certainly had no idea of the scope of Jewish revolt.

Holocaust scholars have debated what “counts” as an act of Jewish resistance. Many take it at its most broad definition: any action that affirmed the humanity of a Jew; any solitary or collaborative deed that even unintentionally defied Nazi policy or ideology, including simply staying alive. Others feel that too general a definition diminishes those who risked their lives to defy a regime actively and that there is a distinction between resistance and resilience. The rebellious acts that I discovered among Jewish women and men in Poland, my country of focus, spanned the gamut, from those entailing complex planning and elaborate forethought, like setting off large quantities of TNT, to those that were spontaneous and simple, even slapstick-like, involving costumes, dress-up, biting and scratching, wiggling out of Nazis’ arms. Some were one-offs, some were organized movements. For many, the goal was to rescue Jews; for others, to die with and leave a legacy of dignity.

As guerrilla fighters, the Polish-Jewish resistance took only a handful of Nazi casualties and achieved a relatively minuscule victory in terms of military success, but the effort was much more significant than I’d known. Over 90 European ghettos had armed Jewish resistance units. In Poland, where many of these were located, the units comprised “ghetto fighters” who used found objects (like pipes), manufactured items (such as homemade explosives), and smuggled-in weapons (including pistols and revolvers) to engage in spontaneous or, more often, organized anti-Nazi assaults. Most of these underground operatives were young, in their twenties and even teens, and had been members of youth movements, which now formed the core structures of resistance cadres. Ghetto fighters were combatants as well as editors of underground bulletins and social activists. The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, I learned, was youth-driven, and strategically planned over months. Most accounts agree that about 750 young Jews participated. (Roughly 180 of them were women.)

Some Jews fought inside the ghettos, but 30,000 (ten percent were women) fled their towns and cities and enlisted in forest-based partisan units; many carried out sabotage and intelligence missions. ‘The Avengers,’ a Jewish-led detachment outside Vilnius, blew up German trains, vehicles, bridges, and buildings. They used their bare hands to rip down telephone poles, telegraph wires, and train tracks. Other Polish Jews joined Soviet, Lithuanian, and Polish-run detachments or foreign resistance units; while others still worked with the Polish underground, often disguised as non-Jews, even from their fellow rebels.

Alongside military-style organizations, Jews organized rescue operations to help fellow Jews escape, hide, or live on the Aryan side as Christians. Warsawian Vladka Meed, a Jewish woman in her early 20s, printed fake documents, distributed Catholic prayer books, and paid Christian Poles fees for hiding Jews in their homes; she also helped save Jewish children by sneaking them out of the ghetto and placing them with non-Jewish families. In Poland, rescue networks supported roughly 10,000 Jews in hiding in Warsaw alone; they also operated in Krakow. Mordechai Paldiel, the former director of the Righteous Gentiles Department at Yad Vashem, Israel’s largest Holocaust memorial, was troubled that Jewish rescuers never received the same recognition as their Gentile counterparts. In 2017 he authored Saving One’s Own: Jewish Rescuers During the Holocaust, a tome about Jews who organized large-scale rescue efforts across Europe. Poland, he claims, had only a small number of these efforts, and still, it was significant.

All these accompanied daily acts of defiance: smuggling food across ghetto walls, creating art, playing music, hiding, even humor. Jews resisted morally, spiritually, and culturally in public and intimate ways by distributing Jewish books, telling jokes during transports to relieve fear, hugging barrack-mates to keep them warm, writing diary entries, and setting up soup kitchens. Mothers kept their children alive and propagated the next Jewish generation, in and of itself an anti-Nazi act. Jews resisted by escaping or by taking on false Christian identities. Roughly 30,000 Jews survived by dying their hair blond, adopting a Polish name and patron saint, curbing their gesticulations and other Jewish seeming habits, and “passing.”

I was fascinated by this widespread resistance effort, but equally by its absence from current understandings of the war. Of all the legions of Holocaust tales, what had happened to this one?

While I researched the lives of Jewish rebels, I simultaneously probed the trajectory of their tales. As I came to find, though there were waves of interest in Jewish defiance over the decades, the resistance narrative was more often silenced for both personal and political reasons that differed across countries and communities. The history of the Jewish underground has generally been suppressed in favor of a “myth of passivity.” Holocaust narratives were shaped by the need to build a new homeland (Israel), the fear of exposing wartime allegiances (Poland), and redefining identity (USA). Early post-war interest in partisans turned into a 1970s focus on “everyday resilience.” A barrage of 1980s Holocaust publications flooded out earlier tales.

Many fighters who survived kept their stories hidden. Many women were treated with disbelief; relatives accused others of having fled to fight instead of staying to look after their parents; still others were charged with sleeping their way to safety. Sometimes family members silenced them, as they feared that opening up old wounds would tear them apart. Many hushed their tales due to oppressive survivors’ guilt: they felt that compared to others, they’d “had it easy.”

Then, there was coping. Women in particular felt a cosmic responsibility to mother the next generation of Jews. They wanted to create a normal life for their children and, for themselves. They did not want to be “professional survivors.” Like so many refugees, they attempted to conceal their pasts and start afresh. The fighters’ formidable tales were buried with their traumas, but both stayed close to the surface, waiting to burst out.

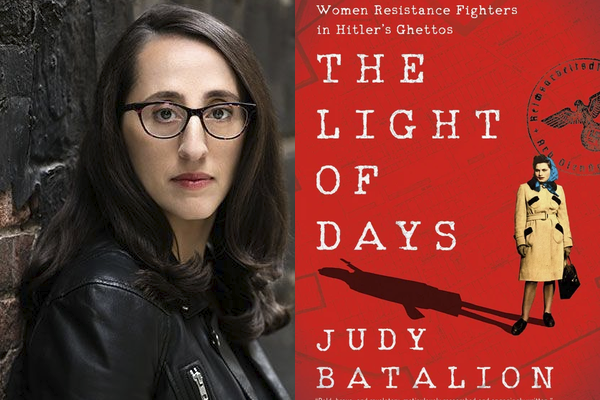

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising began in April 1943, on the first night of Passover. In her groundbreaking book, We Remember with Reverence and Love: American Jews and the Myth of Silence After the Holocaust, 1945–1962, Hasia Diner explains that Passover, a holiday where Jews celebrate liberty, became the time around which American Jews commemorated the Holocaust. However, the uprising element was forgotten. When my book comes out this April, I hope to bring the revolt to the fore once again. I cannot think of Polish Jewry without it; theirs is a story of persistent resistance and profound courage.