Explaining the Different Post-Colonial Trajectories of Ireland and Haiti

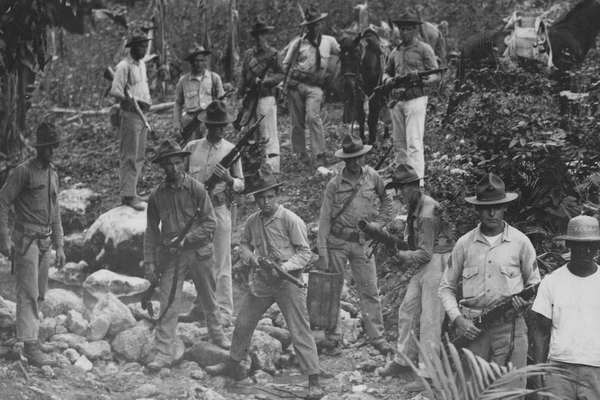

US Marines occupying Haiti, c. 1919

Haiti is frequently in the news, Ireland occasionally so. Haiti is one of the world’s disaster areas. It has been wracked by hurricanes, earthquakes, and political instability. By a number of measures, Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere and one of the poorest in the world. Sixty percent of its population lives in poverty and one-fourth are trapped in extreme poverty. Ireland, on the other hand, is one of the world’s success stories. From the mid-1990s until the late 2000s, the Celtic Tiger experienced phenomenal economic growth. Although the economy has tailed off since then, Ireland continues to have one of the highest GDP per capita rates in the world.

The divergent paths of Haiti and Ireland are rooted in the history of 19th century European colonialism, European and American racism, and the very different alternatives offered to the people of the former colonies for the last two hundred plus years. In both cases, relatively small islands could not support growing populations. The difference was that the white Irish were allowed, or even forced by landowners to leave, while Black Haitians remained trapped on the Caribbean island they share with the Dominican Republic.

Great Britain’s first colony was misruled into the 20th century when Ireland finally achieved independence after a series of wars against British occupation. Even today, six northern Irish counties remain under British control, though this may finally end because of demographic changes and the stupidity of Brexit.

In six of seven years between 1845 and 1852 the Irish potato crop failed because of a fungus, and millions of people starved, died from disease, or were forced to emigrate. With a commitment to laissez-faire capitalist policies and contempt for Irish lives, the British government let Ireland weather a natural disaster with minimal aid, transforming crop failure into famine. Between 1841 and 1880 the population of Ireland plummeted from over 8 million people to less than four million. The estimated population of Ireland today is 5.2 million people.

John Mitchel, an Irish patriot who challenged British control over Ireland charged, “The Almighty sent the potato blight, but the English created the famine.” What Mitchel meant was that crop failure was transformed into famine because the British failed to act to save Irish lives. The crop failure was an act of nature, but the famine was an act of man.

While the Irish Diaspora was experienced as a tragedy, it may have been what eventually saved Ireland. From 1815 to the start of the Great Irish Famine between 800,000 and 1 million Irish emigrated to the United States and Canada. The Great Irish Famine accelerated the Irish diaspora. Almost 2 million Irish men and women arrived in the United States between 1845-55. By the end of the 19th century, as many people who were born in Ireland lived outside the country as continued to live there. Today, people of Irish ancestry make up more than 10% of the population of the United States, Canada, and Great Britain where, despite intense discrimination, they became the industrial workforce at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, and over 30% of the population of Australia, where they were a major part of the European settler population.

Haiti has a very different history. In 1791, a revolt broke out in the French Caribbean colony of St. Domingue, which was located on the western third of the island of Hispaniola. One of the wealthiest colonies in the Americas, St. Domingue, known as the Pearl of the Antilles, produced half of all the sugar and coffee exported to Europe and the United States. It owed its wealth to the work of brutally treated enslaved Africans. The average life expectancy for an enslaved African in St. Domingue was only 21 years, and it was lower for newly arrived Africans transported to the island during the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

The rebellion started when free Blacks in Haiti were not accorded rights promised by the French Revolution’s Declaration of the Rights of Man. Because enslaved Africans and free Blacks outnumbered whites by more than 10 to 1, the revolt quickly spread. Toussaint L'Ouverture, the leading general of the Black revolt, became the undisputed leader of the entire island. Although Toussaint was captured and exiled to France, where he died in prison, the Republic of Haiti became an independent country in 1804, the second independent nation in the Western Hemisphere and the first independent republic governed by people of African ancestry.

The western countries, including the European colonial powers and the United States, would not accept a free and independent Black nation. In the United States, Southern planters feared that the slave rebellion in Haiti could spread and destroy their way of life. The virus of freedom was essentially quarantined. Europe and the United States placed a trade embargo on the new country and France demanded that Haiti repay French planters the modern equivalent of over $20 billion for their lost human property. That debt, partly financed at a profit by a Citibank predecessor bank, was not repaid until after World War II. The United States would not formally recognize Haitian independence for six decades. Closed out of the global sugar market, Haitians turned to subsistence farming on rocky and mountainous terrain that eventually led to deforestation and soil erosion.

In the twentieth century, United States troops repeatedly invaded and occupied Haiti to protect American economic investment, force payments to France, and support dictatorial regimes. The U.S. military has “policed” Haiti at least since 1888, when war boats were sent to “persuade” the government to be friendlier to U.S. shipping interests. Troops were dispatched to protect American agricultural producers in Haiti in 1891 and 1914. In 1910 the American State Department supported efforts by the National City Bank of New York, now known as Citibank, to take control over the Banque National d'Haïti, Haiti’s only commercial bank and its national treasury. In 1915 United States Marines invaded Haiti, secured control over the national capital and government, and occupied and ruled the country until 1934. U.S. economic interests controlled the economy of Haiti until 1947. In 1995, the United States sent 20,000 troops to occupy Haiti and a small military contingent was sent there again in 2004.

Since 2005, over 150,000 Mexicans have legally immigrated to the United States each year, approximately 70,000 Chinese, 60,000 people each from India, the Dominican Republic and Cuba, and fewer than 20,000 Haitians. While Cuban refugees continue to be welcomed, the U.S. Coast Guard turns back people trying to sail from Haiti to the United States.

The only thing that can save Haiti as a viable nation is what “saved” Ireland – mass emigration and a drastic reduction in population to bring the number of people into balance with the environment that must support them. But while the colonial power that controlled Ireland, Great Britain, wanted the Irish to emigrate for its own ends, the United States, the imperialist power that has dominated Haiti for the last century, does not want the Haitians to emigrate because it does not want them to move here. Both the Trump and Biden administrations have supported humanitarian aid and autocratic rule in Haiti, keeping Haiti on life support so they did not have to address the underlying problems.

In 2010, following a massive earthquake, President Barack Obama delivered a powerful statement to the people of Haiti recognizing “Few in the world have endured the hardships that you have known. Long before this tragedy, daily life itself was often a bitter struggle.” He promised, “you will not be forsaken; you will not be forgotten. In this, your hour of greatest need, America stands with you. The world stands with you.”

However, what President Obama did not say was that Haiti was in this precarious position because the United States and the rest of the world not only refused to help the Haitian people in the past, but they established the conditions that made Haiti so vulnerable.