"Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone and Every Close Eye Ain’t Shut": Black Georgians' Memories and Election Unease

During the June 9th primary elections in Georgia, Black voters were alarmed as they stood in line to vote, in some cases for three to four hours. Terri Russell told the New York Times, “I refuse not to be heard and so I am standing in line.” Her dedication was even more poignant as Russell, who is 57 year old and who suffers from both asthma and bronchitis, had requested and never received an absentee ballot, and consequently was risking her life by standing in line during a pandemic in a county with one of the highest rates of COVID-19 cases in the state. Elections officials blamed the problems, which primarily plagued Black and Democratic regions of the state, on new voting machines. For many including Stacey Abrams, the problems harkened back to her narrowly defeated 2018 bid to become the state’s first Black governor, and the nation’s, first Black woman to win a governorship.

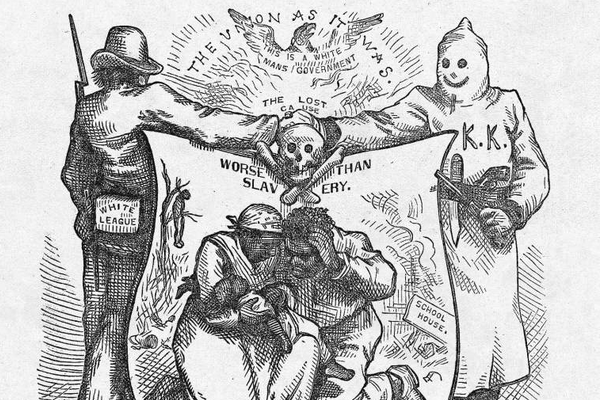

Nearly four months later on September 29th, when Chris Wallace called on President Donald Trump to denounce white supremacist groups like the Proud Boys during the first Presidential Debate, the President responded by calling on the militia group to “stand down and stand by.” For many in Black communities, a collective shudder like steel against porcelain was palpable. The primary elections and Presidential Debate of 2020 remind many in Black communities of efforts to mobilize black voters during the 1960s, but the reality is that semblances of these events reach further back to Reconstruction when formerly-enslaved people were first able to vote en masse. This was a time when millions of Blacks, fresh from the horrors of slavery and the Civil War, held onto the promise that with Emancipation they could participate actively in the American experiment. But In Georgia, it would not be until the Spring of 1868 that they would be able to run for office and vote for laws that they had participated in writing.

In the spring of 1868, African American voters faced long lines at polls when and where polls opened at all. Part of Georgia’s newly ratified constitution was an expansion of education for all Georgians as well as property rights for women, and local white officials frequently questioned Black Georgians’ right to vote. Black Georgians faced tremendous odds to vote, even in regions of the state with Black majorities, and only thirty-three out of nearly two hundred legislators elected in 1868 were Black. Less than five months later, they would be expelled from office because they were Black, and it would be more than a year before they would regain their legislative seats. During that year, White officials throughout the state targeted Black voters with the poll tax. For those who organized politically, their message was clear: the Black franchise was a threat to be quelled. A well-known incident of Black voter suppression was the Camilla Massacre on September 19th, 1868, in Southwest Georgia near Albany. Hundreds of local, primarily Black residents marched to Camilla to attend a political rally, but before they could reach the town square, White residents and officials shot and killed nearly twenty of them while countless others were injured and hunted down as they fled back to Albany.

Efforts to dissuade Black voters frequently materialized in campaigns to threaten both Black voters and Black political leaders who were beaten, often in the dark of night. Others involved in political organizing were held indefinitely in jail with no cause as was the case of F.H. Fyall, one of the Black legislators expelled from office. Fyall was eventually arrested for his political activity and held in jail for nearly two months because of his refusal to switch his political affiliation. Among the more high-profile targets of Black voter suppression were Henry McNeal Turner, a Georgia legislator, a minister and future Bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and sixty-four-year-old Tunis Campbell Sr., a Georgia legislator and an Elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Zion. McNeal faced systematic threats for his political activity and Campbell would find himself incarcerated and on a Georgia chain gang. Blacks were also threatened economically for political activity. Sam Gilbert, a freedman from Houston county, exemplified this suppression when he faced a reduction of his wages for attending a political meeting.

By the fall elections of 1872 the state was firmly under conservative control and state leaders reinstituted poll taxes as a means of discouraging Black voters who already were facing economic challenges due to low wages. Governor James M. Smith legally reconvened the state militia under the guise of promoting peace and civility, and he supplied guns and munitions to state sanctioned militias which were overwhelmingly composed of former Confederate soldiers. During the elections that fall, these armed groups frequently surrounded polling stations bringing violence and intimidation in virtually every part of the state, blurring the line between state sanctioned armed groups and local Klan, and promoting their form of “law and order.”

Black voters and politicians were helpless to oppose state sanctioned suppression, and the number of Black legislators declined even in counties with clear Black majorities. Moreover, Georgia officials, hoping to avoid any return to federal oversight, moved state elections back a month to October and required Black voters to produce poll tax receipts. Unsurprisingly, Ulysses S. Grant again lost the state during his bid for re-election in November of 1872.

For most Georgians, the history of Reconstruction in their state is not a familiar one, but the unspoken realities of past voter suppression in Georgia during this era resonate in the present experience of many Black Georgians. Many have a tacit understanding that, even with the promise embodied in the election of Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012, the past is not gone, but promises to resurface like a shark in deep water with efforts de-register voters or with voting machines that don’t work in black or brown communities. Voter suppression also resurfaces as Black voters are forced to choose between staying at home in an election or risking their lives to COVID-19 by waiting to vote in long lines and endure the potential threat of intimidation by “patriots” emboldened by the President himself to monitor polling stations. 150 years after Emancipation, many Blacks in Georgia and throughout the nation still feel a familiar unease, and many understand the proverb, “Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone, and Every Closed Eye Ain’t Shut”.